Born blind

Sexually-transmitted infections, blindness in babies, and what we choose to see

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently reported that the rate of babies being born with syphilis in the USA is ten times higher now than it was ten years ago. This is a trend that has been seen across sexually-transmitted diseases in the United States: chlamydia and gonorrhea infections rates have seen dramatic increases over the past decade, as well. All three or these bacterial infections are treatable with antibiotics, and all three can lead to serious lifelong consequences if untreated. Gonorrhea and chlamydia can cause both infertility and autoimmune arthritis; syphilis can cause a fatal inflammation of the aorta years later, among other things. These outcomes are very bad, but, again, avoidable: These are all sexually-transmitted diseases. If you didn’t want these things to happen to you, you could just not have sex. Or be strictly monogamous with a strictly monogamous partner. Or always use condoms. And the really bad consequences you could avoid even if you did get infected just by getting yourself tested regularly and then being compliant on treatment.

But congenital syphilis emotionally hits different. The babies who get syphilis before they are born—some of whom will die, others of whom will have serious lasting effects—well, it wasn’t really their fault. They’re just babies, infected by bacteria that corkscrewed their way across the placenta before they drew their first breath. You can’t blame an innocent little baby for their misfortune.

We didn’t always think that way. “Who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?” Jesus’ disciples ask in the gospel of John. The idea that a tiny blind baby might be culpable for his blindness was a live option for people in the ancient world. At minimum, they thought, it must have been the parents’ fault, if not the fault, somehow, of the baby himself.

It is rare for babies to literally be born blind. When they are, it is usually because of an infection they got in utero. Congenital syphilis doesn’t cause blindness in babies, but a maternal infection with rubella or cytomegalovirus during pregnancy can. What is much more common is for babies to become blind after birth, also from an infection.

Helen Keller lost both her sight and her hearing before her second birthday, certainly due to an infection, and probably due to bacterial meningitis. She was blind from a very early age, but Helen Keller was not born blind.

Babies who could never really see because they went blind in just the first few weeks after birth also had infections that destroyed their vision—just earlier in life than Helen Keller’s. This is what it usually meant when it was said that someone was “born blind.”

The top two causes of ophthlamia neonatorum—inflammation of the eyes in newborns, that can lead to permanent blindness—are bacterial sexually-transmitted diseases, just like syphilis is. It’s pretty rare for a baby these days to have ophthalmia neonatorum, though, and even rarer for them to go blind for it, because we treat babies’ eyes with antibiotics at birth.

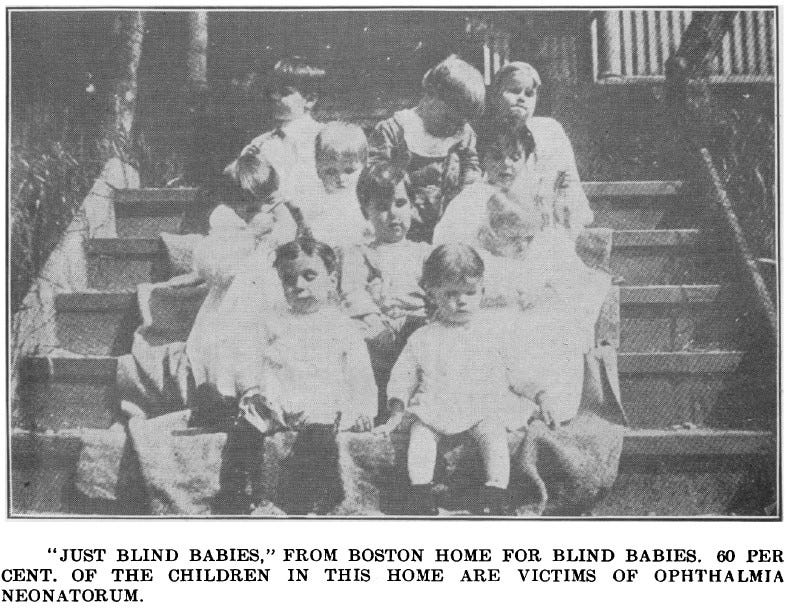

But it wasn’t always. Eye infections with chlamydia or gonorrhea bacteria acquired by babies in the process of being born to an infected mother were probably the most common cause of blindness everywhere until the 20th century, and certainly the most common cause of blindness from birth. Prior to 1880, when doctors first started dosing babies’ eyes with antiseptics when they were born, about one-third of people with blindness were blinded by their mothers’ sexually-transmitted infection, spread to them in the process of being born. Among blind children, the percentages were higher, with close to half of children in schools for the blind having been blinded by ophthalmia neonatorum.

Antiseptic eyedrops for newborns were first recommended in the United States in 1905, at which time about 28% of Americans with blindness were so from ophthalmia neonatorum, Smith and Halse write in Public Health Reports in 1955. By 1950, it was less than 1%. Today, only three babies in 10,000 in the United States develop ophthalmia neonatorum caused by gonorrhea, and just 8 in 1000 from chlamydia. Almost all of these are successfully treated with little loss to vision.

Besides being exposed to it in the process of being born, there is another way chlamydia bacteria can make babies blind—and children, and adults, too. If the bacteria get into your eyes after you’re born, they can cause your eyelashes to flip inward, scratching against your corneas every time you blink, which eventually causes enough damage to make you blind. This condition is called trachoma, and it’s the leading infectious cause of blindness today. It’s spread to the tear ducts by flies, and the flies get it by feeding on chlamydia-contaminated trash. For that reason, trachoma is only found in places with poor sanitation—and in less and less of the world every year. Over the past 30 years, the rate of trachoma has fallen by more than half in the world’s poorest countries, to just about three cases for every 1000 people. Trachoma elimination efforts have been spearheaded by government initiatives and by private charities, notably The Carter Center.

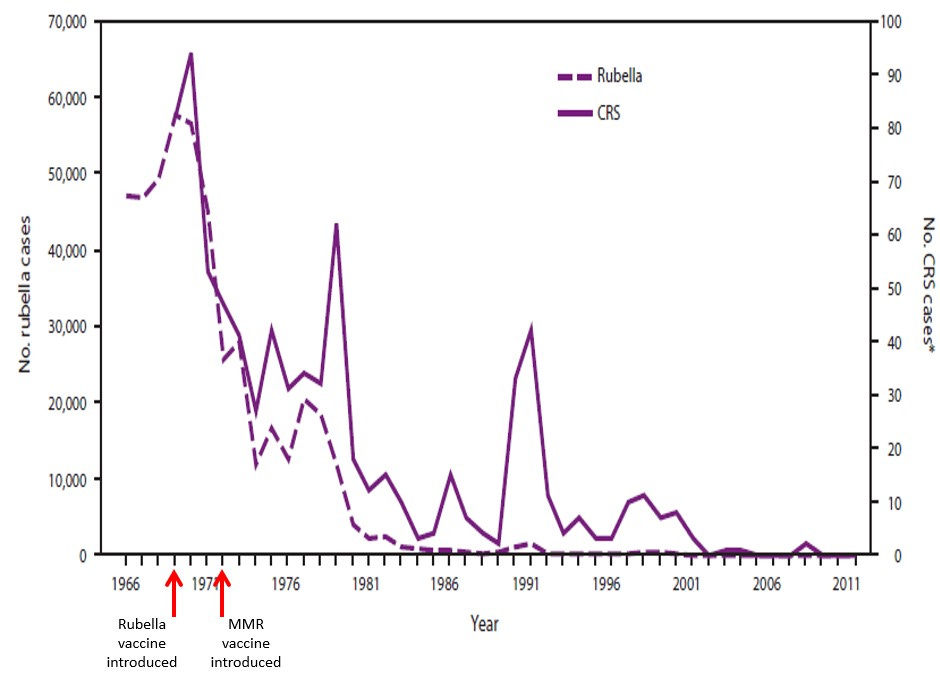

Had she been born today, it is very unlikely that Helen Keller would have become blind. All of the leading candidates for the cause of Helen Keller’s blindness—rubella, Haemophilus influenzae, and Neisseria meningidits—are vaccine-preventable now. Congenital rubella syndrome, once a major cause of babies born blind and deaf (and dying as babies), has been eliminated wherever the vaccine against rubella is widely used.

Vaccination against rubella is now common in most of the world's countries, and as a result, babies born blind from rubella are extremely rare. In 2020, just 603 babies in the whole world were born with congenital rubella syndrome.

So how is it that in just over 100 years we have made blindness in babies go from something commonplace to something incredibly rare?

Of course, a lot of this is about technology: antiseptics, and later, antibiotics, and later, vaccines were developed that would prevent these infections from blinding babies. But the development of those technologies hinged on people seeing those problems as worth solving. And I think that there are a couple of reasons why it took us so long to be able to see babies born blind as a problem that we critically needed to solve.

The technologies that largely solved the problem of childhood blindness—vaccines, antiseptics, and antibiotics—were built to solve a bigger problem: that of massive death rates from infectious diseases, especially among the young. Until about 200 years ago, roughly half of babies born died before their 15th birthday. Most of those died before they were five years old. Against this bleak backdrop of tragedy, it was hard to discern the fainter problem of children who merely could not see.

But there was still a delay between when technologies to prevent blindness in babies were invented, and when they were widely adopted. The connection between gonorrhea in a mother and blindness in her baby was established as early as 1750, and the use of silver nitrate eyedrops for its prevention was shown to be effective in 1880. But antiseptic eyedrops for babies weren’t widely used in the United States until fifty years later. A safe and effective vaccine to prevent rubella infections—and with it, congenital rubella syndrome—was invented in 1969, but as late as 1980, there were only three countries that were routinely using this vaccine: the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands.

I think this is because it is hard to see problems that are not our own.

In the United States, an epidemic of rubella in 1964-65 led to at least 11,000 miscarriages, 2100 stillbirths, and 20,000 surviving babies born with congenital rubella syndrome—an event impossible for Americans to miss. But in other countries, where rubella epidemics were not raging, the problem of congenital rubella may not have been as visible. In the United Kingdom, rubella vaccination was initially limited to girls, as the problem of babies getting birth defects was not seen as one for boys. We have come increasingly close to eliminating rubella and the birth defects it causes as we have come to see it as a problem to be solved for everyone—boys and girls, in rich countries and poor ones—rather than just for some.

But there’s another thing that I think was going on, as well: when we see something that makes us uncomfortable, we have a tendency to just turn away.

In an essay in The Kansas City Star in 1914, Helen Keller makes this case. Pleading for funding of a campaign to provide antiseptic eye drops for babies, she writes that physicians not wanting to frankly address sexually transmitted infections has hampered efforts to prevent eye infections in newborns:

“Physicians and workers for the blind in many states have tried to have articles on the subject published, but they have invariably found it difficult. They have been informed that the matter they wished to print is ‘indecent, shocking.’ …Let us put away false modesty and silly prejudices and try to understand the enemy we are fighting….Ophthalmia neonatorum is a venereal infection….It is a pity when things that bring such terrible consequences to the children of men may not be discussed in the public prints for fear of offending somebody’s modesty. We shudder at the mere mention of the dread disease, but we keep on building hospitals and asylums for the blind, the deaf, the feeble-minded, and when we look upon these monuments to our shame, our sensibilities are not shocked.”

Four years earlier, making a similar argument for using antiseptic eye drops in newborns in The American Journal of Nursing, Carolyn van Blarcom bemoans the “sin of omission” on the part of scientists and physicians in not informing mothers and midwives of the cause of ophthalmia neonatorum, but declines to name it as a sexually-transmitted disease herself.

When something is painful to look at, I think there’s another natural response as well: to find a reason the victims of the problem are in some way to blame. That won’t fix the problem, but it can give us, its witnesses, a reason to look away.

Both Carolyn van Blarcom in The American Journal of Nursing in 1910 and Helen Keller in the Kansas City Star in 1914 are careful to establish that the babies afflicted by ophthalmia neonatorum are not to blame. “It is never difficult to stir emotions and raise funds for the relief of sufferers from some great disaster, earthquake, mine explosion, or what not,” Carolyn van Blarcom writes. “Shall we have less compassion for utterly defenseless babies, so pitifully dependent upon our care and protection?” Helen Keller, unafraid to name the cause as a sexually-transmitted disease, also assiduously claims the innocence of mothers: “It is a specific germ contracted in cohabiting with prostitutes which the mother has received from contact with her husband previous to the birth of her child.” That prostitutes themselves might be mothers to babies born blind is not a topic Helen Keller wants to broach. I suspect she feared that observation might weaken public support for her goal of preventing blindness in babies.

“Most men do not sin wantonly. I firmly believe that the majority of mankind wish to be decent to their offspring,” she adds.

“My countrywomen, this is not faultfinding. I am not a pessimist, but an optimist, by temperament and conviction,” Helen Keller wrote on the same topic to The Ladies' Home Journal in 1901.

By 1955, every state in the United States mandated that antiseptic eyedrops be administered to neonates by the midwife or physician attending the birth. By the 1990s, this was replaced by less-irritating erythromycin ointment in the United States, although the original silver nitrate eyedrops are still widely used around the world. And blindness in babies caused by ophthalmia neonatorum is now largely a thing of the past.

“Who sinned?” the disciples ask Jesus before he heals the blind man. They would not have known this, but we do: it is most likely that the cause of anyone being “born blind” from antiquity up until the 20th century was a sexually-transmitted disease. If they want someone to blame, they would not be wrong to blame the blind man’s parents that he was born blind. Of course, placing blame correctly is not the point.

We are not so different from the disciples in this story. We, too, when confronted with tragedy we cannot unsee, want someone to blame. For congenital syphilis, we have a variety of options: We can blame the mother, for getting the infection, or for not seeking testing and treatment for it, or both. We can blame the government, for not adequately funding public health programs that would have allowed her to more easily be tested and treated. We can blame the pharmaceutical industry for not producing enough penicillin G, the drug of choice to prevent congenital syphilis, because of its low profit margin. We can blame physicians for failing to consider alternative drugs for preventing mother-to-child transmission of syphilis in the face of penicillin G shortages. There is plenty of blame to go around, and none of it is misplaced. But placing blame and then looking away cannot be the point.

We succeeded in preventing blindness in babies as we started to focus more on solving the problem for those babies rather than narrowly focusing on our own perspective. I think that something similar may explain the recent increase in rates of syphilis and other sexually-transmitted diseases, and could bode poorly for blindness in babies in the future.

First, we need to be able to see a problem as a problem. Our stunning success against infectious diseases in the past century—including syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia—can lead to complacency. Against the brilliant backdrop of those successes, it’s hard to see when we start to slip. As syphilis has become more rare thanks to our efforts, demand for the drug to treat it dropped to the extent that drug companies stopped producing enough of it to treat the cases that did exist. And then rates started to rebound. The same thing has happened with ophthalmia neonatorum: our success in fighting gonorrhea and chlamydia eye infections in newborns has resulted in another shortage of erythromycin eye ointment as happens periodically.

As Helen Keller inveighed against in 1914, I think that we are again too shy in our discussion of sexually transmitted diseases. Rather than the prudishness that stopped gonorrhea from being explained as a cause of infant blindness in the early 20th century, I think our reticence now comes out of a different impulse. Knowing that shame has stopped people with sexually-transmitted infections from seeking medical care in the past, I think that there’s a laudable inclination to not want to contribute to shaming or blaming the person with the disease. But that has led to us feeling uncomfortable frankly addressing the risk factors for diseases like syphilis, or the consequences of those infections. While sexual activity overall has markedly declined over the past 20 years, especially among young adults, risky sexual behavior seems to have increased for those who are getting sexually-transmitted infections. I think this is tied to a general societal reluctance to say “monogamy is safer than having multiple sexual partners” or even “syphilis can kill you.”

But the biggest thing I think explains our massive successes against these diseases in the past, and why we are starting to slip now, is an increasing tendency to see ourselves as atomized individuals responsible only for ourselves rather than members of a society with obligations to others.

The rhetoric of early campaigns to eradicate ophthalmia neonatorum are rife with appeals to the public good, and perfectly willing to use the power of the state to get prophylactic eyedrops in babies. Today, however, universal use of antibiotic ointment for newborns is increasingly opposed, with a preference for individualized choice. Rubella vaccination, long seen as a public good to protect babies, is seen now by nearly one-third of American adults as an individual choice, “even if that creates health risks for others,” according to polling by the Pew Research Center. Across the board, campaigns to prevent infectious diseases—sexually transmitted and otherwise—focus on the benefits to you, the individual, without mention of any broader social good. Today, the technology we have to prevent infectious diseases is as good or better than that or our forebears. What’s worse is our solidarity.

Babies are born unable to focus their eyes, and can’t really see their world until they’re eight weeks old. They don’t develop the ability to consider the perspective of others until they’re toddlers. Empathy is a characteristic of grown-ups.

We are all born blind to the problems of others, but as we grow up we can choose to see. Our sin is in deciding not to.