The weather is always erratic when there is a hurricane coming through the Caribbean, even when that storm is hundreds of miles away. The wind swirls instead of being directional, and the sky hovers in a space between sunshine, spitting rain, and a downpour. I think you’d be able to tell something is amiss somewhere even if you didn’t have modern technology pinging you with updates to confirm your suspicion. And of course, it’s all anyone is talking about.

“Real busy hurricane season, supposed to be this year.”

“You know, they say there’s never been a category 5 so early before.”

“Pray for the Grenadines.”

The word for “hurricane” sounds the same in most European languages: Spanish, huracan; German, hurrikan; Finnish, hurrikaani; French, ouragan; Italian, uragano; Dutch, orkaan; Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian, orkan. This is because European languages did not have a word for this sort of storm prior to European contact with native Caribbean peoples—they didn’t have storms as massive or violent as the ones that regularly scour the Caribbean islands, and so they didn’t have a word for that phenomenon. So Europeans borrowed the local word for this kind of devastating storm: the Taino word “hurakan,” meaning “the god of storms.”

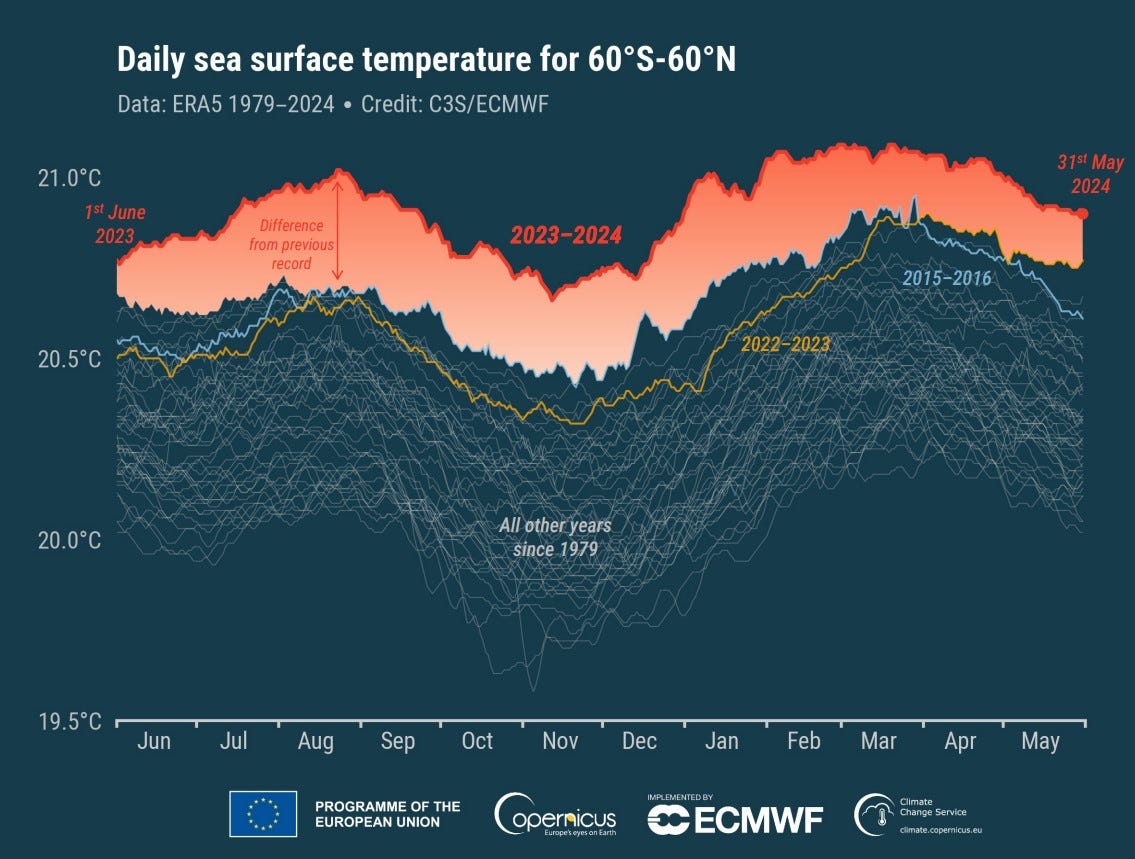

“It’s scary, for true it was August water temperatures already back in May.”

It is scary. I’m not a meteorologist so don’t understand how, but hotter ocean surface temperatures are thought to enable the formation of storms. That’s why hurricane season is defined as running from June 1 to December 1, with August and September the riskiest months, since that’s when the water is the warmest. Last year was one of the most active hurricane seasons on record, and every prediction is that this year will be more active still. And if things keep going the way they’re going, we can keep expecting these records to be set, year after year.

So far I have only been through two hurricanes, six years ago: Hurricane Irma, followed a few days later by Hurricane Maria. Hurricane Irma was the most powerful Atlantic hurricane ever recorded, at the time. It held on to that record for two whole years.

“Where do you evacuate to, when there’s a storm? Do you go back home?” No matter how many times I am asked this, I am amazed at this assumption that there is a place for the people who live here to evacuate to, that this is not our home.

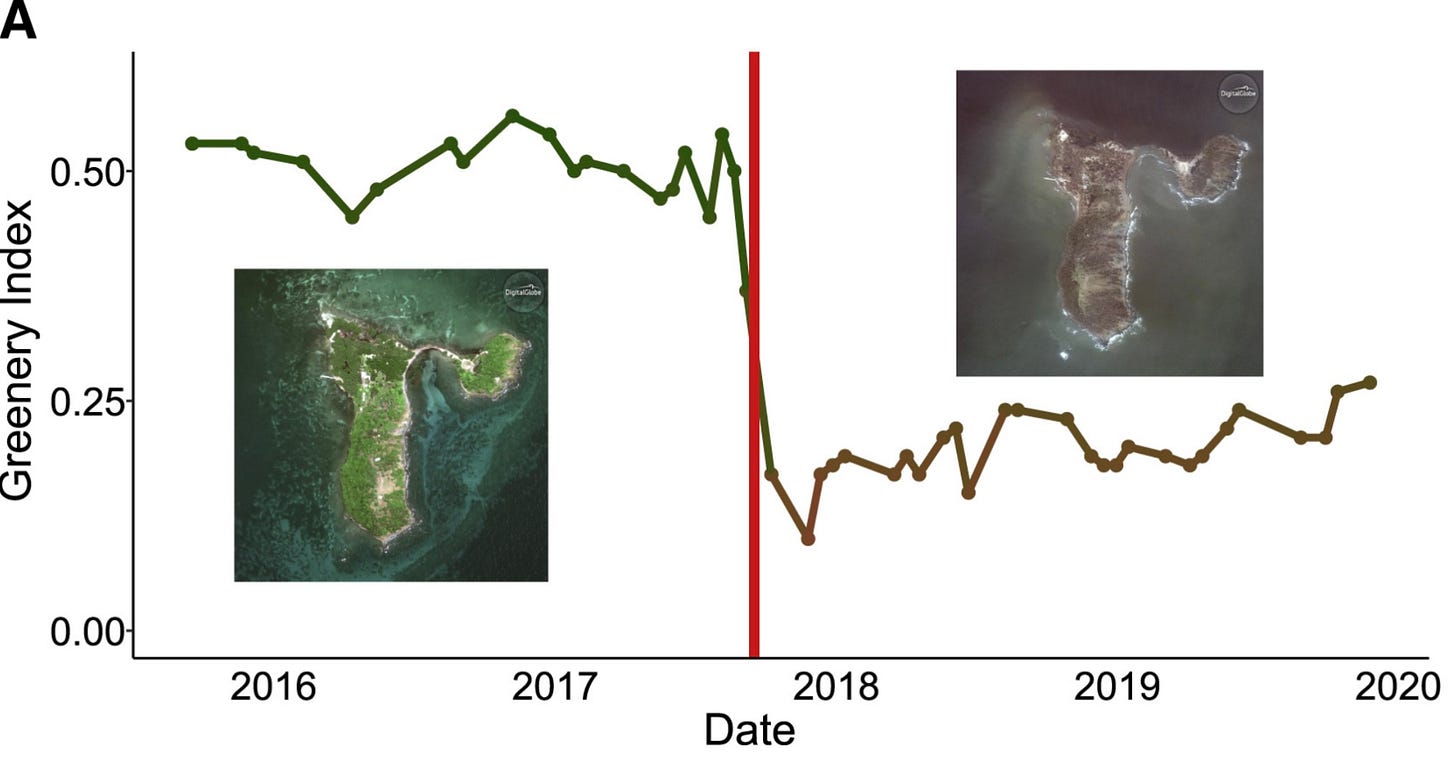

Hurricane Maria grazed us, but it hit Puerto Rico hard. In addition to the many displaced humans, the monkeys lost their homes. Testard et al. described the effects of Hurricane Maria on the monkeys of Puerto Rico in an article published last month in Science.1 Their team had been observing the behavior of macaques2 of Cayo Santiago, a small island off the coast of Puerto Rico for over 10 years—both before, and after, the devastation caused by Hurricane Maria. Macaques have a hard time regulating their body temperature, and hurricanes take out a lot of trees. Normally, macaques seek respite from the heat in the shade of the rainforest, but that would be hard for them to do after the storm, now that most of the rainforest was gone. Testard et al. had a lot of existing data about the social behavior of the monkeys before the storm made landfall, and they made a prediction:

Shade became a scarce and critical resource after Hurricane Maria. On the basis of evidence showing increased competition when resources are scarce or monopolizable (15–17), we predicted that, after the hurricane, rhesus macaques—who are widely regarded as among the most despotic of primate species (18)—would display lower social tolerance and more frequent aggression.

That is what one would predict, right? In the aftermath of Irma, when all the lights went out in St. Maarten, across the way, there were reports of looting and it was generally accepted among my friends here that society had collapsed there. Because that’s how things really are, right? Nature is red in tooth and claw, and survival of the fittest, just like Darwin said.3 Everyone knows that in a crisis, everyone just looks out for himself, and maybe his own kin. Kindness and cooperation are just a thin veneer laid over our selfish nature we share with the animals. It would be naive to imagine otherwise.

But that’s the opposite of what Testard et al. found.

Our island got off pretty light from Irma and Maria in 2017. A few houses had their roofs torn off, but no one was seriously hurt. Last week, Beryl didn’t touch us at all. We’ve been really lucky.

After the 2017 hurricanes, while folks on my island were repairing their own houses, we were also collecting supplies to send to the badly hurt islands, like St. Maarten. This was a little dicey, since all our supplies are shipped in through bigger islands—including St. Maarten and Puerto Rico, which had just been demolished. It wasn’t entirely clear where we would be re-supplied from, given this situation.

But you can’t just hoard things for yourself because you’re uncertain about the future when other people are in need now. Have some faith. Consider the lilies of the field and the birds of the air. They’ll be fine, and so will you.

But the birds of the air were not fine following the hurricanes. Hurricanes kill birds in massive numbers, in the violence of the storm itself, and in the resource deprivation that follows. The destruction of the foliage from a hurricane starves the birds and takes away their shelter. The wild bird populations on our island have still not recovered from the hurricanes of 2017.

Meanwhile on Cayo Santiago, Puerto Rico, the monkeys were also suffering. Almost two-thirds of the tree cover had been destroyed, and the influx of water from the storm had cut the little island into two smaller ones, also sorting the macaques into separate populations.

So what did the monkeys do in the face of this catastrophe? Well, they became a lot more social.4 On average, monkeys spent more time hanging out with each other and grooming each other after the hurricane than they did before. The most anti-social monkeys prior to the storm had the largest increase in pro-social behavior. Almost all of the monkeys expanded their social circles. They still spent time with blood relatives, but proportionally spent less time grooming their kin after the hurricane, because they were so busy getting to know their new friends.

The monkeys became much more tolerant of other monkeys following the storm. Relationships became less hierarchical, with grooming more frequently reciprocated between previously dominant monkeys and those lower in the pecking order. Aggression was reduced. Sharing of resources increased.

But what about competition, survival of the fittest? The primate researchers continued to observe the monkeys of Cayo Santiago, and here is what they found:

We found that monkeys were persistently more tolerant of others in their vicinity and less aggressive for up to 5 years after Hurricane Maria. Relationships based on social tolerance became more numerous and predicted individual survival after the storm, especially during the hottest hours of the day….

Social tolerance after the hurricane was associated with a 42% decrease in mortality risk, an effect comparable to the survival impacts of social support in humans.

Poor dumb monkeys. I guess they haven’t been told that in a crisis, it’s only the selfish who survive.

When I was younger, I always thought it was dumb when people would talk about the weather. It seemed like the kind of milquetoast topic that people who wanted to avoid offending others would have as a conversation topic—the smallest of small talk. I wanted to talk about deep things like philosophy, and have arguments with people about important things like politics.

Once, when I was a kid on a debate team, I was on a political talk radio show discussing the politics of climate change.

Can you even imagine? What an absolute place of ignorance and privilege, to talk about the climate but not the weather.

The Latin American and Caribbean region contributes to less than 7% of global carbon emissions, a lower rate of greenhouse gas production than would be predicted based either on our population or on our economic productivity.5 All of the Caribbean islands put together are responsible for less than three-tenths of one-percent of global carbon emissions. Yet our homes are among the places very most at risk of destruction from the effects of global climate change, from rising sea levels and from hotter oceans and the hurricanes they make.

On my island, most of our electricity is solar. We use cistern water and take navy showers. We are much more likely to repair something that is broken than to replace it, and we recycle and compost and grow gardens. But we do not control the weather.

Our own individual virtue cannot save us from natural disasters. We must rely on other people who do not know us, who are less at risk of catastrophe themselves, to solve this global problem. We are, as all living things ever were, dependent on the kindness of strangers. Even a monkey can figure that out.

On my island, we collected supplies to send to the victims of Hurricane Beryl, just like we did before for the victims of Hurricanes Irma and Maria. We donated money.6 We prayed the hurricane prayer.

People online bicker over small talk. While Beryl’s victims try to survive the shared effects of a real storm, political debates are increasingly fragmented and theoretical, while billionaires speculate about consciousness outside a physical body, or colonies on Mars. As if there is a place to evacuate to, as if this is not our home. As if there is anything worth discussing besides the weather.

For the Taino, Hurakan was the god of storms. God comes to us in the whirlwind, too, a pillar of fire, a pillar of cloud. Always, the message is the same: the only way to survive is to look beyond yourself. We are all in this together, whether we believe it or not.

Testard et al., (21 July 2024), “Ecological disturbance alters the adaptive benefits of social ties,” Science 384:1330–1335. DOI: 10.1126/science.adk0606

If you wonder what the old world monkey species of rhesus macaques were doing on a Caribbean island, the short version is that they were imported, like a lot of things were to the Caribbean. The slightly longer answer is that 409 macaques were introduced to Cayo Santiago in 1938, for reasons that I’m sure were clear to the people who dropped them off there. For whatever reason, this is how there’s a primate research center in Puerto Rico that has collected so much data on macaque behavior.

“Nature red in tooth and claw” is actually Alfred Tennyson. “Survival of the fittest” is actually from social Darwinist Herbert Spencer to make the point that (1) evolution is true and (2) capitalism is the scientifically correct moral order and we don’t have to do anything to take care of poor people. Neither of these phrases appear in any original edition of any writing by Charles Darwin. Poet Tennyson was channeling a lot of the same ideas Darwin had, however. There’s a nice history of this by Kenneth Weiss in Evolutionary Anthropology 19:41–45 (2010).

Testard et al. (7 June 2021), “Rhesus macaques build new social connections after a natural disaster,” Current Biology 31(11):2299-2309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.03.029

OECD (2023), Environment at a Glance in Latin America and the Caribbean: Spotlight on Climate Change, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/2431bd6c-en

Samaritan’s Purse is a Christian charity with an established presence in the Caribbean and an excellent track record of providing hurricane relief. The American Red Cross is also excellent, but of course focused on the United States. In any case, it’s much more effective to contribute to an established charity that has experience in a particular region than to new organizations with less expertise. If you can’t decide, just throwing cash at people affected by climate disasters is a pretty great option, too.