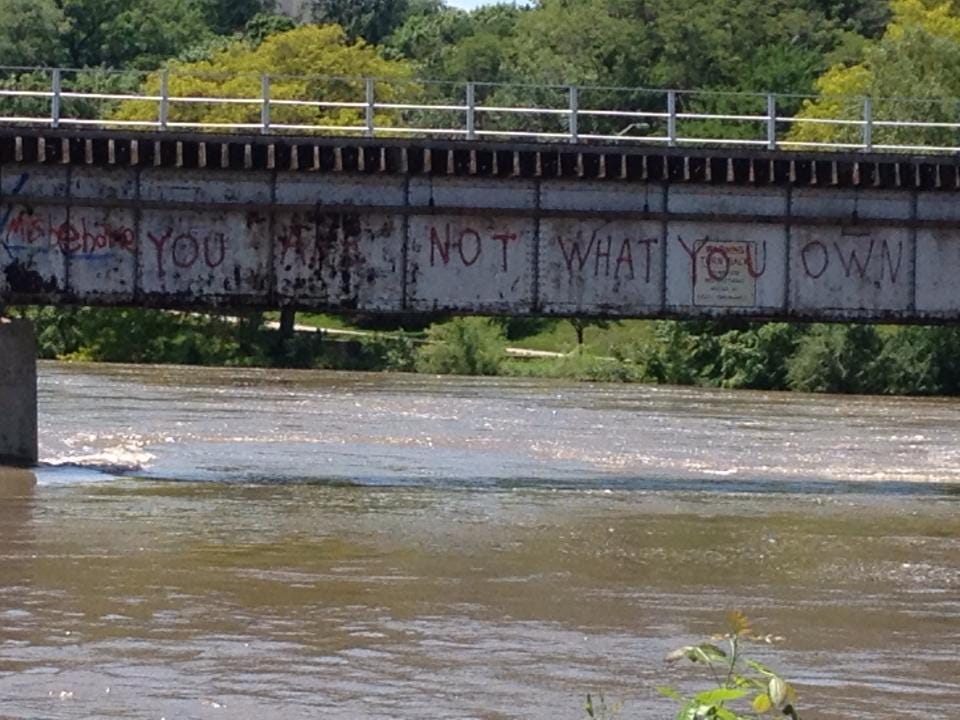

The summer after I lost my job, I spied this graffiti on a bridge in the city I lived in then. In the Chuck Palahnuik novel, this phrase shows up as graffiti, too. I don’t know if this the person who painted this bridge was quoting Fight Club, or if they were both quoting a common source.

Whatever was going on, it was what I needed to see at the time. I was in the process of selling most of my possessions to facilitate moving to another country for a new job. I had defined myself through the job I had lost, which I did not yet understand was a mistake. I am grateful for my anonymous friend who left this note for me. The fact that comforting me was almost certainly not the graffiti painter’s intention does not make that person less of a friend.

And I was in need of friends. Where I was going, I would be leaving my friends from work—these people with whom I had shared so many important experiences—behind. I miss them still.

I live in my new country now, and have for longer than I worked with those colleagues in America. I still keep up with most of them on social media. They seem to be doing well—although, of course, that’s what social media shows you, isn’t it? I hope they are doing at least as well as their posts convey.

Another thing I see a lot of on my American-dominated social media feed is memes like this:

In the United States, there seems to be an ascendant narrative that the smart, savvy thing to do is to see your coworkers as your competitors, and not get bogged down by worrying about their personal lives or letting them see yours. That’s the most efficient way to earn money, and that’s the only thing a job is for. People you work with can’t be trusted with your vulnerabilities. Friendship is for suckers.1

It’s ironic that this explicitly pro-corporatist sentiment is being promoted even on ostensibly pro-workers Reddit threads—what could be more detrimental to organizing attempts than convincing employees that they shouldn’t trust each other? The more disturbing thing about this, though, is that anyone would rather see their own value as a maximally-efficient cog in an impersonal system, rather than through their relationships with other humans with whom they share a large fraction of their waking hours and experiences. What do you do when you’re sick? What do you do when you’re suffering? The system will not save you.

When I lost my job in 2012, it was those relationships with coworkers that helped save me. I had invested so much of my self-worth in being the best worker in my company, bragging about my long work hours and accomplishments. I didn’t know how to define myself outside of that system.

At the time, a friend from work gave me this poem by Mary Oliver, that ends:

Tell me, what else should I have done? Doesn't everything die at last, and too soon? Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?

I don’t know that she ever knew how much that last question helped me.

Later, she left the company we had both worked for, too. Her increasingly few social media posts indicate she’s happy—though again, who can really say. I wish I had been able to do something for her as supportive as that poem was for me.

Not every one of my friends from work was as supportive. A common response to another’s misfortune is to look for a reason why the bad thing happened to them, and will not to you—a kind of whistling past the graveyard. I think the more precarious one’s own situation is, the more desperate the need to believe in the justice of the system. So when I lost my job, a lot of my work friends looked for reasons why I deserved it. I don’t blame them; I’ve done the same thing in similar circumstances.

When entire industries shutter, we tell the dispossessed to learn to code and ourselves that they should have been more adaptable to a dynamic economy, whistling away.

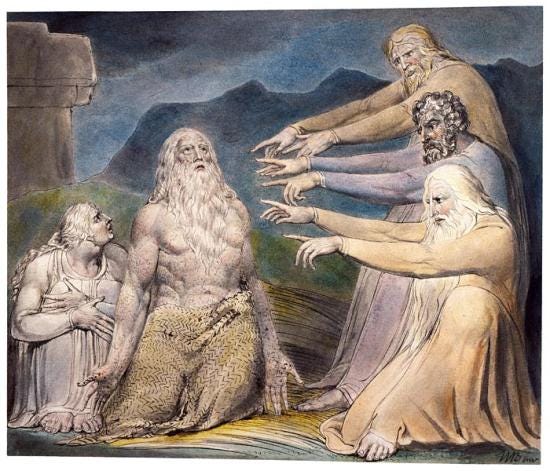

The story of the book of Job goes like this:

Chapter 1: Job is an unimpeachably good guy

Chapter 2: Horrible things happen to Job which the reader knows are in no way Job’s fault

Chapters 3 - 37: Job’s friends explain to him that all the horrible things that happened to him must actually be his fault, and Job disagrees

Chapters 38 - 41: Poetry about nature that reads like something by Mary Oliver

Chapter 42: The horrible things that happened to Job are all reversed, and God chastises his friends for saying that any of this was his fault

A lot of scholars claim that the book of Job is about the problem of evil—i.e., why a good God allows bad things—but 34 of its 42 chapters don’t involve God saying anything at all. They’re about friends telling someone who’s suffering that he deserves it, rather than comforting him.

I don’t think Job’s friends meant to hurt him. They were just weak, and terrified, and looking out for themselves. I, too, have hurt friends by not being strong enough to witness their suffering without judgment. I, too, have offered explanations rather than compassion, or have just looked away.

In chapter 42, when Job pleaded to God on behalf of his friends, were they relieved, or ashamed?

The prediction that more and more jobs will be lost to automation is commonplace, and that those white-collar jobs in coding that manual laborers should have flexibly transitioned to if they’d only been more clever will soon be replaced by AI. I suppose that would render any discussion of whether one should be friends with their coworkers moot.

Last year,

offered an even more disturbing prediction about an AI-enabled future in his haunting essay, Laughing with Kittens:[I]n the next decade our best friends will be generated by AI.

They will know us intimately, instinctively, predictively, compassionately. They will have an uncanny ability to generate trust, demonstrate empathy, coach, cajole and create in us the profound experience of being loved. They’ll text us when it’s just the right time, send us charming memes. They’ll listen with full attention. Offer perfect advice perfectly. No human can compete.

This will all happen while we look into our goggles and stare at our phones, sliding further down our personal rabbit holes. Our relationship with sentient human beings will be altered.

Our loved ones already compete for our attention with mindless videos and downloadable applications. There is a fundamental shift happening, and it is a question of how soon and to what degree, not if.

In Fight Club, The Narrator imagines Tyler Durden into being because he, too, wants the perfect friend to lead him down his self-centered rabbit hole, from which only mayhem can emerge.

But the comforting graffiti on the bridge was real.

When scholars talk about “the problem of evil,” they aren’t asking why a good God allows people who do bad things. That’s easy: people are selfish and scared, and end up hurting others as a result. The problem of evil is usually cast as the problem of natural evil: why are there hurricanes, floods, cancer diagnoses—naturally-occurring horrible things? And I don’t know the answer to that, but I do know that we are embodied beings who live in that natural world, subject to all of that violence.

And that’s what friends are for.

Neither Tyler Durden nor the most gifted chatbot can help you navigate the stairs on crutches when your bones are broken. They will not sit with you in the doctor’s office. They will not make you your favorite meal when you are sick. They will not help you put up the hurricane shutters, and they will not help you clear the debris after the storm is passed.

But you know who will do all those things? My friends from work.2

The summer after I lost my job, I had a cancer scare and the city flooded. A former coworker I didn’t know well helped me clear out my house and clean up the yard. I’ll never be able to return the favor; I've completely lost track of him, and even if I hadn’t, I live in another country now. I will also never be able to repay the friends who listened to my rants about the injustice of it all, who never tried to explain away my pain. But friendship isn’t a quid pro quo; it’s a gift.

What I can do is give that gift to others. I can’t reverse the times that I wasn’t a better friend in the past, but I can help with the hurricane shutters and comfort the friend with cancer right now. And this is the problem with the logic of why I shouldn’t be friends with my coworkers, and and why I will be with a bot: the value in friendship is not merely in feeling cared for, but in caring for others.

Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon? Whistling past the graveyard with savvy tricks to work the system will not save you. But we can save each other if we stop being selfish and afraid.

Cynicism is for suckers.

And not just at work. Friendship is down and loneliness is way, way up across domains in the United States. This interactive visual summary of data from the American Time Use Survey on The Pudding is very informative.

I know some Americans may make the objection that any of these physical acts of caring can be purchased through a service, probably through an anonymous interaction with an app on a phone. I feel sorry for them.

Damn I loved this. Extremely good shit. I’ve always felt that it’s really inhuman the way we are supposed to compartmentalize all the parts of our life and keep all the people separate. It is, of course, also a sin against God to be cynical in a world so full of beauty and mystery.

Poignant. You remind me of why I do interviews, even though there is no evidence to suggest that they convert free subscribers to paying members. It is being in conversation with someone for an hour -- or longer -- that feels worthwhile. Following that thread, being present to them. It's like the hour of silence I hold with others in my Quaker meeting, which is another kind of conversation (ironically).

I also produced a grant-funded podcast for two years with a colleague. We somewhat masochistically decided to gather two-hour oral histories from our guests that we then tried to reassemble, through rearranging and narration, into <1hr episodes. The editing nearly killed me, but I still remember how glorious it was to speak with someone else for those two luxurious hours. AI can't do that.

Wynton Marsalis once said that the definition of "soul" is that feeling you have while visiting someone's house, when you don't want to leave, you want to stay longer. It's worth more than almost anything else.

Here's that podcast series: https://www.midamericana.com/