The potluck had been canceled because the host was ill, so instead my husband and I spent the afternoon cutting each others’ hair and dyeing mine (hey, it’s not vanity, it’s just wanting to look like I look like, and I don’t look like someone with that much gray hair). I also tore all the hair out of my legs and armpits, because, again, I want to look the way I feel I should look like, and no pain, no gain.

I used to pay for this sort of thing. Before, I went to salons to yank the hair out of my legs and pamper the hair on my scalp. My husband would also go for a haircut, and sometimes a shave. We’d give money to strangers to pour hot wax on my skin, or to hold a razor to my husband’s throat. We trusted that these strangers would render the services requested, and not hurt us, because of course we did.

But when you hand yourself over for a shave and a haircut, you’re putting yourself under the power of someone who could do grievous physical harm to you so quickly that you wouldn’t be able to escape. It’s worth noting this because while it is obviously true, the observation sounds crazy. What kind of paranoiac would actually be afraid that the girl at the SuperCuts is going to go all Sweeney Todd on them?

Humans are not unique in trusting others to make them look pretty. Animals groom themselves and other animals all the time. Birds do it,1 bees do it,2 and even educated fleas should know to stay away from animals who groom each other if they know what’s good for them, because a key benefit that animals get out of being groomed is the removal of parasites.

It’s less clear what the animals doing the grooming get out of it. Reciprocal altruism is a popular explanation—“If you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours,” but very literally. In primates, researchers have also speculated that the monkeys doing the grooming reap social benefits by cozying up to monkeys higher in the social hierarchy. Animals who groom each other (this is called “allogrooming” in mammals or “allopreening” in birds) tend to have more cohesive social structures than similar animals who only look after themselves. This whole set of advantages is described as “social capital:” A macaque who picks the nits off another macaque banks social capital that can be drawn upon at some point in the future, in the nitpicker’s time of need. Surely, this argument goes, there must be some selfish reward that the groomer gets, because otherwise, why would she do all this labor? As if the only way we can understand what goes on in apple trees with honeybees and snow-white turtledoves is by analogy to capitalism3.

And indeed, when I’ve pointed out how charming it is that we trust strangers to wield dangerous tools right next to our scalps in the service of beauty, I’m reminded that hairdressers are being paid—as if that’s an explanation. As if the only thing that protects us from some Hobbesian war of all-against-all is that there’s money to be made in being nice to each other. I think the opposite is true: We took an existing task that runs on deep trust and turned it into paid labor only because we already trusted each other.

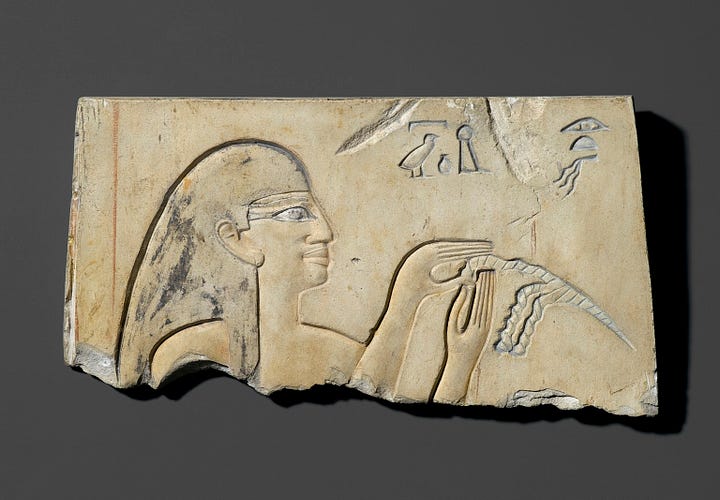

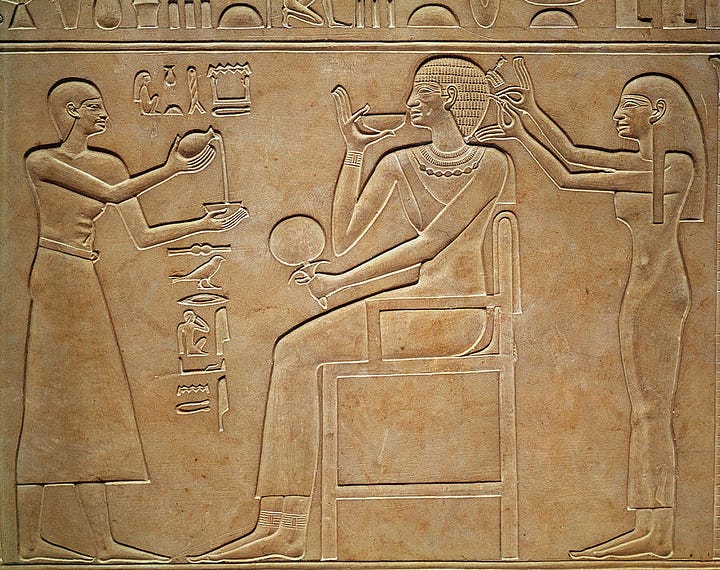

Hairdressing has been around as a paid profession for a long time—at least the past 4000 years. For almost all of that time, violence has been much more common than it is now, both at the level of state-sponsored wars and on the level of individual homicides. But even in times and places where violent death was hundreds of times more likely than it is anywhere in the world today4, and lacking the policing power of law enforcement, the Better Business Bureau, or negative Yelp reviews, people still cheerfully submitted themselves to the hairdresser’s comb and the barber’s razor.

Curiously, human hairdressing doesn’t seem to get counted as “allogrooming” by people who write about these things, even though it obviously is. When applied to animals, the phrase “social grooming” means one animal neatening the fur or feathers of another animal, possibly with social benefits. It is a synonym for “allogrooming.” When applied to humans, “social grooming” refers just to people taking actions to maintain friendships, like returning calls and texts and party invitations and bringing something to the potluck.5 I get the impression from my brief review of the literature on this that a key reason why going to the hairdresser does not count as allogrooming is because you pay her for it.

Like a lot of people, my husband and I stopped paying other people to groom our hair during the first part of the COVID pandemic, because we had to. But by the time that ended, the salon I had gone to had closed, and the post-pandemic economy of our very small community has not rebounded enough to replace it. So now I get my hair done by strangers as a luxury, when I’m on vacation.

And it is a luxury, to submit yourself to the ministrations of someone who does not even know you, and who you will probably never see again. The logic of reciprocal altruism is that nice things are done so that nice things can be expected in return, as individuals have repeated interactions with each other over time. When I have my hair done by professionals, this isn’t true—but the exchange of money for service allows us to pretend that it is. We trust in the system of monetary exchange to provide an incentive for the unknown hairdresser to treat me, a one-time client, well.

Except I’m not trusting capitalism to do my hair and not harm me; I’m trusting an individual person, just as she’s trusting me not to skip out on the bill. The exchange of money for grooming is just a symbol in an interaction that is far more profound than a crass capitalist quid pro quo.

But the capitalist metaphor that informs our interpretation of grooming behavior of animals I think also infects our interpretation of our own social behavior as humans. We interpret monkeys picking parasites off each other as merely the acquisition and spending of social capital, and similarly view our own interactions in a capitalist economy as merely getting what we pay for. Especially post-COVID, western societies seem to increasingly divorce a purchased service from its social interaction. So we order restaurant food from an app, never exchanging pleasantries with a waitress. We bank online, and never have to exchange eye contact with a cashier. We have mistaken the monetary metaphor of reciprocal social interaction for the thing itself, and we are much poorer for it.

At least now, hairdressing—the most mourned of COVID-closed industries at the height of the pandemic—requires social contact. Though where I live, the salon remains closed, so it’s up to me to get out the clippers. I’m happy that we’ve developed enough skills that my husband and I can provide this service for each other, but I miss S., my stylist when the salon still existed.

By the next weekend, our friend is feeling better and the party is back on. I make a salad again, we bring a bottle of wine. Our host makes the delicious goat stew he always does. But equivalent exchange of food was never the point; that was just a mechanism for allowing us to enjoy each others’ company.

Humans are the most pro-social of mammals to have ever existed. We are so social that we invented things like money and metaphors so we could maintain and expand our social universe. We were having parties long before we invented the idea of payment-for-service. We’ll be doing so after the modern economic metaphors we use to rationalize our social behavior have been long forgotten. And, as long as we have a little help from our friends, we’ll look great doing it.

See, for instance, Villa et al., “Does allopreening control avian ectoparasites?” Biology Letters, (July 2016). 12(7), doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2016.0362

Cini, A., et al., “Increased immunocompetence and network centrality of allogroomer workers suggest a link between individual and social immunity in honeybees,” Scientific Reports (2020). 10, 8928. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-65780-w

I do appreciate the irony of citing a Coca-Cola ad to complain about interpreting everything through the lens of capitalism. That ad always make me cry, though—it’s just so beautiful.

While it’s hard to accurately counts violent deaths in the ancient world, we can know for certain that the past was much, much more violent than the present. This article from Our World in Data does a nice job summarizing some of the data we do have on deaths from violence in past cultures. In comparison, the country with the highest homicide rate on earth right now is Jamaica—whose roughly 50 murders/100,000 population/year pales in comparison.

For non-human primates, “social grooming” also includes maintaining friendships, but this is measured by allogrooming. For application of models of cooperation developed by observing non-human primates to people, where “social grooming” just means “hanging out with,” see, for example, Takano and Ichinose, “Evolution of Human-Like Social Grooming Strategies Regarding Richness and Group Size,” Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, (2018) 6. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2018.00008

You might like Pinker’s “Better Angels of our Nature” book.

We probably share many things in common, but one of them is Footnote 3. That ad was a special ad and really made an impression me as a child. Briefly mentioned below. I include the link as proof, not as a reading assignment. :-) Besides, you have a scientist's regard for citation. Thank you for sharing your work with me.

https://www.adamnathan.com/p/threshold-i