I moved from the Midwestern United States to the Caribbean island I now live on 11 years ago. This makes me an “ex-pat.” “Ex-pat” is a polite term that means “an immigrant with money.” I fit this bill: I moved here because I was hired by an international company into a well-paying job that could not be filled by a local. “Ex-pat” also has a connotation of being temporary in a way that “immigrant” does not; it’s expected that the “ex-pat” will go “home,” back to the country she was born in after some amount of time overseas. It’s almost as if the “ex-pat” is on an extended vacation. In this respect, I do not fit the bill. If I ever leave Saba, it will be in a box1. I love this island. This is my home.

“I never felt patriotism about a place like I do about here,” a fellow ex-pat told me, tears in his eyes, at our last Saba Day celebration. All I could do was hug him and nod. I was too overwhelmed with gratitude for my adopted home to say any words.

There are many things about Saba that make me love it so much: Its history and culture; its natural beauty; its warm community. I even love Saba’s political issues2.

A major political issue on Saba is the management of feral goats. Goats were first imported to Saba early after its discovery by Europeans, and became an important food animal almost immediately. Goat husbandry is an important aspect of Saba culture. It is also the case that free-ranging goats on Saba destroy a lot of property, and overgraze on native plants, resulting in erosion. Goats are considered an invasive species on Saba by Dutch3 specialists who do not live on Saba. For this reason, a government-funded effort to bring in goat hunters from other countries to eradicate the feral goats was initiated. This was moderately successful, and very controversial.

What are goats on Saba? An alien invasive species destroying the natural environment, or an essential element of Saba culture that outsiders want to eliminate? From my own perspective, I’ll observe that the landscape looks a lot better when there are fewer goats, but it’s more fun to see more goats around. Also Saba goat is delicious.

Regardless of one’s views on goats, protecting the natural beauty of Saba is a major community concern. There are multiple island clean-up events and other volunteering opportunities every year to help preserve the environment and keep the island looking pretty for tourists. I helped with the cleanup of a beach that is a major nesting site for red-beaked tropicbirds. Saba is home to the world’s healthiest population of red-beaked tropicbirds, which are badly endangered or have been driven to extinction almost everywhere else.

Some years back, there were worries that cats were preying on tropicbird populations, so a major effort was put into place to trap or kill stray cats. The cat population declined—and so did the population of tropicbirds. It turns out that another imported species, rats, were the major predator of tropicbird babies, not cats. Crashing the cat population allowed the rats to raid tropicbird nests with no fear of being killed themselves.

What are cats on Saba? An alien species destroying native populations, or a defense against alien species destroying native populations?

In addition to the tropicbirds, there are at least 100 other species of birds that live on Saba. There are five species of reptile. Saba has as much biodiversity as it does because it has multiple microclimates, and because it’s an island: isolated populations of animals can undergo “population bottlenecks,” restricting genetic diversity and leading to the evolution of new species. Two of Saba’s reptile species are unique to Saba, the Saba anole and the Saba black iguana.

How did the founders of the Saba anole and iguana populations get here, I wondered. The island itself is less than one million years old, so it’s not like they evolved here on their own, from the time of the dinosaurs. It turns out that some smaller land animals like reptiles can be blown from one island to another by hurricanes. Wild, isn’t it? Can you imagine being a lizard on one island, being scooped up by the wind, and dropped miles away on another island, having to make a life for yourself there? But that’s the standard model of how the reptiles of Saba first got here.

It’s not clear when the ancestors of the Saba black iguana were first blown onto the island by a storm, but they were first noted as a distinct population in 1879, and formally recognized as their own endemic species in 2020.

Recently, a few green iguanas from neighboring St. Maarten arrived on Saba. This is an environmental concern, because the common green iguana might interbreed with the Saba iguana. As invasive species researchers at Wageningen University write:

Saba is home to one of the last remaining native Iguana populations in the Lesser Antilles that, until recently, was not directly threatened by non-native iguanas. ….The iguana population was found to be larger than initially expected and occurred island wide, even though feral cats (predation) and goats (erosion and habitat degradation) are major threats…. The most urgent threat, however, is the presence of alien iguanas.4

When the first iguanas that would evolve into the Saba black iguanas blew onto the island, what other animals did they displace, through competition or interbreeding? At what point would they have been considered the invasive species? When a Saba black iguana mates with a common green iguana, how much of the baby is a threatening alien iguana, and how much is a protected endemic iguana?

One of the reasons Saba has the pristine natural environment it does today, with its abundance of species, is that it could never successfully be turned into sugar cane plantations like other Caribbean islands were. The island is so geologically new that the soil conditions are too poor for anything beyond subsistence agriculture. So our island was not permanently inhabited by any native people at the time of discovery by Europeans, and it also did not pan out as an economic investment for Europeans the way many other islands did. The original immigrants to Saba had to figure out how to subsist on the island for themselves, and Saba’s rainforest was never cut down.

With the lack of soil on Saba, in the rainforest many plants grow perched on rocks, like this:

This is one of the many species of Xanthosoma, or American “Elephant Ears,” that grow on Saba. The original Xanthosomas to come to the island were probably blown here by storms, just like the iguanas. Xanthosoma species produce both underground roots when they can, and “aerial roots” when they can’t. The aerial roots absorb enough moisture from the very humid air to allow the plant to survive. But the aerial roots aren’t latched to the ground, the way underground roots would be. So another strong storm can blow the plant away, maybe even to another island.

Eventually, if the aerial roots hit soil, they will penetrate the soil and develop into underground roots. Depending on how high up the plant is on her perch, this could take years. If the aerial roots break or get cut away, the plant has to start over from scratch. It seems like an act of defiant optimism, growing aerial roots with no way of knowing whether they will ever hit soil. It feels like a mad act of hope, this longing to put down roots.

Some species of Xanthosoma are considered invasive, weeds. They’re too good at making themselves at home in the places to which they’re blown.

As much as I love Saba’s ecology, the thing I love the most is Saba’s community. When one of my (indoor!) cats got lost outside, a lot of our community members helped me to find him. When I was volunteering with the beach cleanup, I was there with dozens of my neighbors, who might bitterly disagree over correct goat management or any other political issue, but are proud to come together to help make our island a better place. Saba is a place where you leave your house and your car unlocked, where small children hitchhike and strangers are invited to community parties, where everyone cares about everyone else.

A lot of us are immigrants.

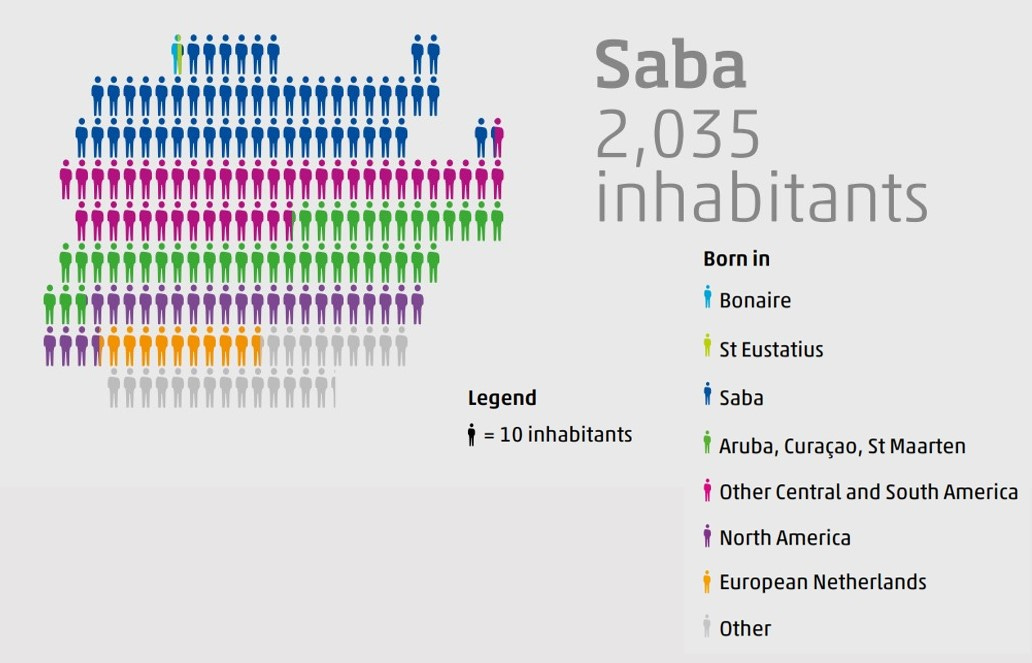

Of the just-over 2000 people who live on Saba, about half were born outside of Saba, the Caribbean Netherlands, or the Netherlands overall.

At least 40 different nationalities are represented on Saba. On the graph above, “other” includes people from France, the United Kingdom, South Africa, Nepal, and Lebanon. There is a substantial population of Filipinos on Saba as well.

So how did we all get here?

Well, speaking for myself, I came here for a job. I had lost the job I had in the United States, and was increasingly desperate to find a way to not lose my entire career, and of course to pay my bills. I applied for a job here, and I got it. Many of my fellow immigrants to Saba have similar stories.

Like the rest of the Caribbean, Saba was originally settled for economic reasons, and like the rest of the Caribbean, most of the earliest old world immigrants came here for reasons outside of their own control. The Caribbean was settled by enslaved people from West Africa, indentured servants from India and the British Isles, and occasional political prisoners. Sure, there were European explorers and investors who came to the islands, too, but they didn’t stay. They didn’t have to. They could just go home.

Caribbean islands are not the only islands onto which new residents are blown, without a lot of their own agency.

recently reported on research regarding resettlement of Indonesian islands. The Indonesian Transmigration Program forcibly moved families into new homes on a variety of islands in the 1980s. While the aim of the Transmigration Program was to make similarly ethnically diverse communities in all the places people were resettled, some communities ended up being much more diverse than others. This had lasting consequences. Dr. Evans writes of the study by Bazzi et al.:5“The haphazard resettlement process generated significant variation in diversity even across nearby settlements with similar natural advantages”, explains Bazzi and colleagues. Inadvertently, some neighbourhoods became highly ‘polarised’ (comprising two big ethnic groups), whereas others were more ‘fractionalised’ (featuring multiple small ethnic groups).

This initial random assignment had long-lasting effects. Even decades later, this initial mixing significantly reduced the level of ethnic segregation within villages.

So how did those fractionalized, very ethnically diverse communities turn out? Well, they forged their own identities as members of a community. The people who ended up in the communities with lots of ethnic subgroups became more cohesive, cooperative, and patriotic. They were more likely to speak Indonesian at home than their particular ethnic first language, and they were more likely to trust each other. They intermarried, had mixed-ethnicity children, and made themselves at home.

The opposite was true of the communities with just a couple of ethnic groups. The less diverse communities became polarized, with mutual distrust building between the two dominant groups. People of different identities self-segregated, and didn’t speak to those in the other ethnic group. People in the polarized communities were less likely to help their neighbors, and less likely to contribute to public goods. They also felt less safe. They were not at home.

Both the fractionalized and polarized Indonesian communities were the same in that they were comprised of individuals who did not choose to be there. But there was a huge difference in how those individuals chose to interact with others in the place where they landed.

In a moving essay about place and the nature of home,

discusses the idea that Americans are “boomers” or “stickers”—those who set out like pioneers on quests of discovering greener pastures, or those who put down roots in the place they were born. These terms were coined by Wallace Stegner, who, with American authors Wendell Berry and Scott Russell Sanders, praised the virtue of being a “sticker,” committing to stay, and make the place you were born in your home. But, as Dr. Dolezal observes:So I wish for more honesty from Stegner, Berry, and Sanders about how much privilege and luck it requires to stay put, in addition to effort and sacrifice. Sanders held tenure at a flagship university in Indiana during the best years in higher ed. Stegner and Berry likewise developed their ethic of rootedness only after securing livelihoods largely independent of local economies.

…While Berry and Sanders frequently credit their wives with building homes that enabled their success, neither author says much about what Tanya Berry or Ruth Sanders gave up to allow their families to stay put.

Indeed, staying in one place for one’s entire life is as much a product of fortune as leaving is. And the group of people most likely to have had to leave the place of their birth and make a new place their home has been women. Throughout history and across cultures, women have been uprooted from their natal homes to travel with husbands from other places. Today, economic migrants are still more likely to be women than men. It’s so much more common for women than men to leave the place of their birth that there’s a term for it in demography: female migration.

Sometimes these women have chosen the places they left for, but more often they have not. They chose to travel with their new family, and the place just came along as part of the package. The men they were traveling with may have been seeking economic opportunity, but the women’s role, when they got to where they were going, would be to raise children, prepare food and clothes, and contribute to the social life of the community.

The word for such a person is a home-maker.

A friend of mine, an American citizen whose parents immigrated to the United States from Europe and Asia when she was a child was telling me about her experiences as a third culture kid, how as an adult she lamented a tie to an ancestral home. She likened putting down roots to the roots of an ancient oak tree, stolid and mighty, each branch of the tree connected to the same kin, the same earth. But that’s not actually how roots work. Roots don’t just connect the tree to the earth. Roots connect the tree to other trees. It’s harder to see on an oak in America than it is when I look at roots here, but the reality is the same:

Roots latch into the earth, but mainly they latch on to each other. This is easy to see where the soil is very shallow, keeping roots above ground like they are on Saba. A tree that isn’t rooted to other trees’ roots will blow over in a storm. It might blow to another place and grow again, but it might just die.

You can’t just put down roots into a place; they won’t hold. The only way you can put down roots is as part of a community. To do that, you have to help others, and let them help you.

If you want to have a home, you must become a home-maker.

In a widely-circulated essay on Americans living in other countries,

writes:For most expats, it’s often a one-way conversation about all they’ve taken and how they’ve benefited. Rarely, if ever, is it about how they’ve contributed. The people who came to build something—a family, a life, a career—enriching their present lives, not hiding from their old ones, are few and far between.

And as an ex-pat, this made me think: am I an invasive alien, or am I an immigrant, helping to enhance the diversity and resilience of my community? Am I a goat, a cat, a green or a black iguana, an elephant ear plant? Because this is where I want to make my home. This is where I want to put down roots.

So I had better close this essay, because I have work to do. There are events to volunteer for, repairs to do, pies to make for potlucks, and neighbors to help. I should be thinking right now about how to help with the next 5K, community Christmas caroling, and of course the next Saba Day.

Being at home isn’t about choosing the place you love and living there. It’s about choosing to love your place, wherever life has blown you. Saba is my home. And home is where my heart is.

I am again indebted to

and his writing on invasive/immigrant species at . This essay also was influenced by home-maker ’s writing on her move to Norway.Or an urn. But I couldn’t be buried here. There’s not enough land in the cemeteries for people who do not already have family plots.

I am not ignorant of the real problems. The primary school needs restructuring, the medical referrals system is a mess, and don’t even get me started on the whole Winair is a public utility that should also for some reason have to follow a growth model bit.

Saba is a “special municipality” of The Netherlands, meaning it kind of has the political status of a Dutch city. We can elect our own Island Council members, but not a Saba representative to Parliament. We have closer ties to The Netherlands than other Dutch islands in the Caribbean that are more famous, like St. Maarten and Aruba.

“Faster recognition of non-native iguanas on Saba helps Caribbean conservation efforts,” Press release from Wageningen University and Research, March 28, 2023.

Bazzi, S. et al. (2019). “Unity in Diversity? How Intergroup Contact Can Foster Nation Building,” American Economic Review, 109(11): 3978–4025.

Really enjoyed this! It's interesting that ex-pat typically comes with an assumption of returning to the original patria. I knew many ex-pats in Costa Rica who felt much as you do. There were reasons they left, and going back held no appeal. I've felt something like that in Prague and in Moravia. I could see how someone might move there and never return.

I do think that if someone has a stable community in a place that they also love, then that is a rather special exception to your rule. Otherwise, I agree that a lot of it is about intentionality and leaning into the possibilities wherever we are.

"Being at home isn’t about choosing the place you love and living there. It’s about choosing to love your place, wherever life has blown you."

Yes, this is so true. I've lived in many different places over the course of my life; ultimately, my home is in God's hands, but until I'm called back there I choose to love whichever place I have been granted, for howsoever long it is mine.