A family of doves has been nesting in my office window since January. The second generation of parents came in June, and their babies—the fourth set to be hatched in my window this year—just flew away. It’s given me a good opportunity to learn about doves, which I really knew hardly anything about before I was given this gift.

Here are some things I have learned: Doves are excellent at nuclear families. Pairs of doves mate for life, and both parents contribute equally to childcare. Both the mother and the father feed the babies—not partially-digested and regurgitated food, as many birds do, but “crop milk,” a specialized secretion for feeding babies produced in response to prolactin by a gland in the birds’ gullets. It is rich in protein, fat, and the antibody immunoglobulin A as well as normal flora bacteria. “Crop milk” is thus very similar to mammalian milk, just made by both sexes and not in the breasts.

Here is the father taking care of the newly-hatched babies and, in a later video, feeding them. You can tell it’s the dad and not the mom because of his lavender-gray shading on the shoulders. He’s also a bit bigger than the mother bird is.

Here are the parents trading nest-sitting duties, when both eggs had been laid but only one had hatched yet.

I can hear from my desk when it’s time for a shift change, because they call to each other with soft coos. Doves can recognize their mates by the sound of their voices, and their babies can recognize the sounds of their parents’ voices, too.

I’ve read that they’re called “mourning doves” because their voices sound sad, but I think their voices are pretty. It’s also the case that when a dove’s mate dies, the survivor mourns. I saw this happen when a mourning dove was killed flying into one of our sliding glass doors at home. Her mate kept calling for his beloved, inconsolable. My husband and I buried her in the flowers—it seemed like the least we could do.

I know, that’s foolishly sentimental—but being sentimental about animals is about the most human thing there is.

Humans have a long and storied history of using animals to inform our interpretation of human behavior. In earlier times, animals represented virtues which people could emulate or vices they should avoid: the courage of a lion; the loyalty of a dog; the pride of a peacock; the sloth of a, um, sloth. Today, we are more sophisticated: We tell stories about what human nature is based on analogy to other animals. This is because we now understand evolution. Unlike those dummies in the past who saw stereotyped animal behavior as a moral lesson designed by God, we can make claims about how humans ought to behave based on our common ancestry with other animals. So what are we really like?

#notalllobsters

According to psychologist Jordan Peterson, we are like lobsters.1 We are hierarchical and fight over limited resources. For lobsters, according to Peterson, a key resource is territory, and a male lobster wants a territory all of his own. Peterson writes,

This can present a problem, since there are many lobsters. What if two of them occupy the same territory, at the bottom of the ocean, at the same time, and both want to live there? What if there are hundreds of lobsters, all trying to make a living and raise a family, in the same crowded patch of sand and refuse?

Thus, to establish and maintain his territory, the male lobster will try to exert dominance over other lobsters, through hormone release, signaling displays and claw-to-claw combat, if necessary. The lobster who loses such a battle has his brain chemistry rewired consistent with his loser status, and the winner goes on to have sex with all the lady lobsters. Humans use the same hormones and neurotransmitters as lobsters do, and lobsters are evolutionarily successful, with things like lobsters having been around for at least 350 million years or so2. So fighting and dominance is just the way humans are, like lobsters. That’s science.

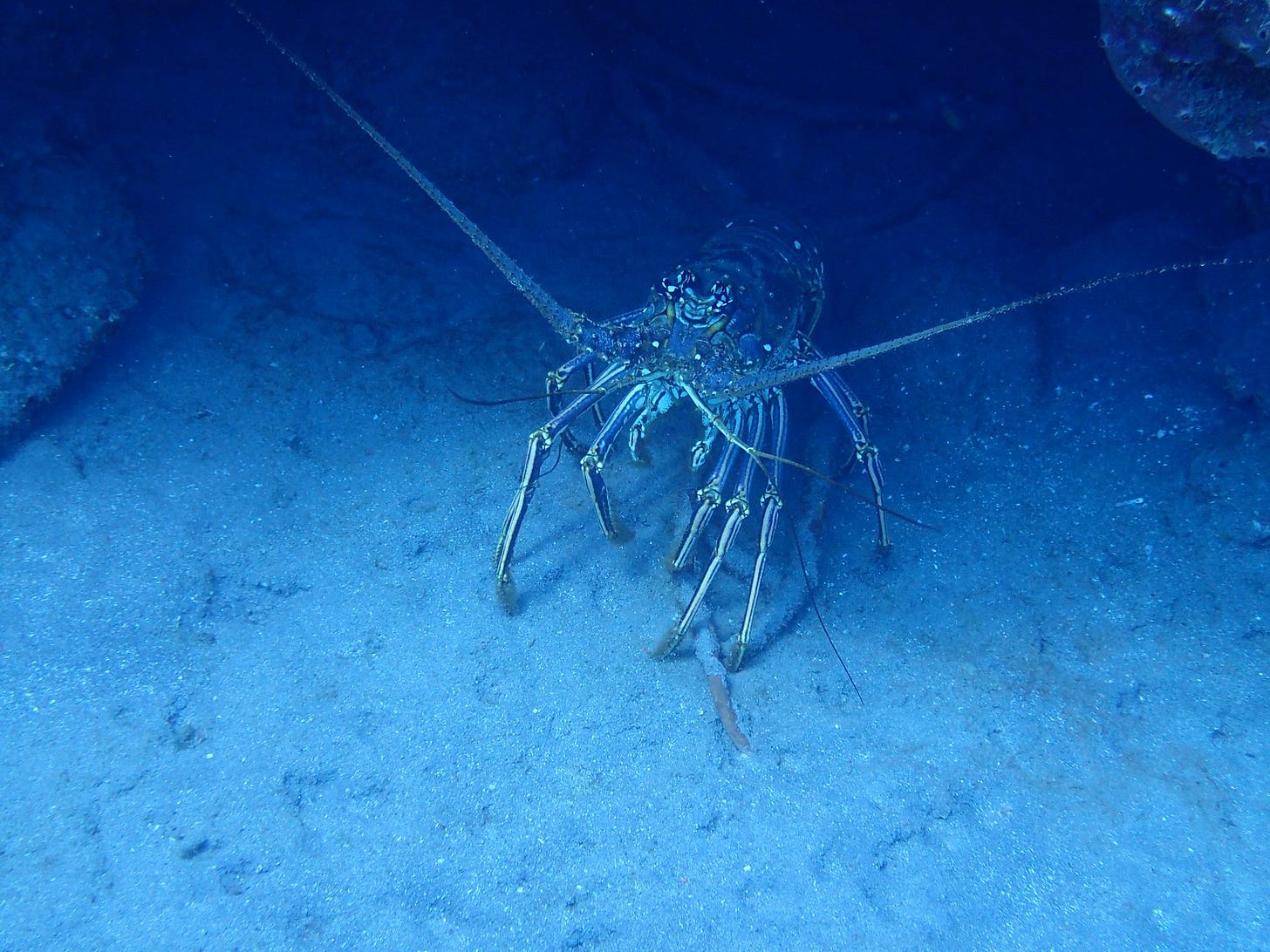

Dr. Peterson is a Canadian, and he is describing the North Atlantic American lobster, Homarus americanus. Where I live, lobsters are different. For instance, they do not fight with their claws, because they do not have claws.

Because they do not have claws, spiny lobsters (Panulirus argus) are preyed upon by tropical fish called triggerfish, which have powerful jaws that can bite through lobster shells. To defend themselves, spiny lobsters hide in collective dens under rock outcroppings and coral reefs. When they need to migrate somewhere, they move by the hundreds or thousands. They are attracted to approach other Panulirus lobsters through chemicals in their urine. The same kind of hormone signaling that made American lobsters exert dominance and fight each other causes spiny lobsters to cluster together to fight triggerfish, using elaborately coordinated collective behavior. Panulirus lobsters form choreographed “queues,” “rosettes,” and “phalanxes” to keep each other safe from the triggerfish foe. Instead of using claws to engage in combat with other lobsters, spiny lobsters use their attenules—the spindly homologues of claws seen in the photograph above—to keep in close contact with their friends. They will stay in groups to defend each other even in an experimental setting where one lobster is tied down to a platform in an aquarium with a predatory triggerfish, and the others are free to escape.3 The only thing that has seemed to make them avoid each other is fear of catching a plague; Panulirus lobsters avoid the dens of lobsters infected with PaV1, a deadly viral disease of lobsters discovered in 2000. As a result of this, some note that young adult lobsters have become markedly less social since approximately 2013.4 And haven’t we all?

American lobsters and spiny lobsters last shared an ancestor at least 100 million years ago. Whether North Atlantic American lobsters or Caribbean spiny lobsters, lobsters are arthropods. Humans are chordates. Thus, the most recent common ancestor that we share with lobsters is the ancestor of the entire eumetazoan group—animals with actual tissues (that’s what makes one a eumetazoan)—about 700 million years ago.

If you are a lobster, what kind of lobster are you? The kind who cooperatively fights predators with his comrades, or the kind who literally loses his mind if he fails to monopolize a patch of sand?

The problem of evil, and wasps

As humans, we are at least as closely related to wasps as we are to lobsters. As with lobsters, wasps come in a variety of species, and have a variety of different social behaviors.

There are two species of wasp I see frequently on this island: the “Jack Spaniard” paper wasp, Polistes crinitus, and a “cicada killer” wasp, Prionyx thomae. They’re both gorgeous, but they have very different behaviors. This difference in behavior is why I’m much more afraid of the paper wasp than the cicada killer—though I’m sure I would feel differently if I were a cicada.

The paper wasp is social, welcoming, altruistic—at least with respect to other paper wasps. Unable to recognize blood relatives as such, paper wasps form loose-knit groups of “foundresses”—reproductive females who can start to build a papery nest of processed plant fibers as a nursery. While one foundress does most of the egg-laying, her fellow foundresses have some babies, too, and they all care for their young collectively. Their babies are mainly girls. Unlike with many other bees and wasps, they all have the potential to become fertile foundresses themselves—there isn’t a caste system of nonreproductive workers serving a single queen.5

Also, paper wasps are extremely aggressive in defense of their tiny hives, which they really like building under the eaves of our house and on rock outcroppings all around my favorite hiking trails. Their sting feels like being shot with a BB, but that is also on fire. The last time I was stung, it was on my calf, and my leg swelled up enough that I couldn’t bend my knee for a couple of days.

The cicada killer is a loner. She’s also misnamed—as an adult, Prionyx thomae eats nectar from flowers, and hunts crickets and grasshoppers to provision her babies. Her sting paralyzes her prey, which she drags back to a hole in the ground. She places the cricket in the hole, and lays her egg in its living body. Her baby carefully consumes the body of the cricket as she grows, avoiding any bite that would kill her host until she is ready to emerge as an adult from its body.6

The biology of parasitoid wasps like Prionyx is commonly credited with causing Charles Darwin to lose his faith in a benevolent God, underscoring the problem of evil. As he wrote to his friend and fellow naturalist Asa Gray in 1860,

I own that I cannot see, as plainly as others do, & as I should wish to do, evidence of design & beneficence on all sides of us. There seems to me too much misery in the world. I cannot persuade myself that a beneficent & omnipotent God would have designedly created the Ichneumonidæ with the express intention of their feeding within the living bodies of caterpillars, or that a cat should play with mice.7

Hymenoptera, the group that includes all wasps, bees, and ants, began to evolve just a bit later than the lobsters did, around 280 million years ago. Lobsters are evolutionarily successful, but wasps are more so, comprising tens of thousands of extant species. Hymenopteran social behavior is often collectivist, and always female-dominated. Curiously, the wild success of hymenopterans, with their queens and their communism, has not typically been held up as evolutionary exemplar of how humans really are and how we should behave.

The snake in the garden

There is just one species of snake that lives on my island, the Leeward island racer, Alsophis rijgersmaei.

Racer snakes are lovely. Shy and completely harmless to humans, they hunt small lizards and rodents during the day, and rest at night. Alsophis snakes avoid each other, too, unless they’re mating. They are completely beneficial from a human perspective.

That has not stopped them from being driven to extinction across almost all of their native range, however. Once common across all of the Caribbean, they’re now found on only a few islands, and only have a healthy population on one.

Humans and racer snakes are much more closely related than humans and lobsters, or humans and wasps. Our most recent common ancestor lived around the same time that lobsters were first evolving, 325-350 million years ago.

Snakes are never used as an example of what human nature is really like, or how humans should behave. Despite their relatedness, they’re just not relatable. Instead, snakes are used as symbols of cunning and evil. Even on my island, a common response to finding an innocent racer snake is to kill it.

Jesus also used animals as metaphors for human behavior in his teaching. As he was sending the disciples out into the world to evangelize, he said,

See, I am sending you out like sheep into the midst of wolves; so be wise as serpents and innocent as doves.

And like a lot of Jesus’ teachings, I don’t understand entirely what this means. I do know that I’m not really a dove, or a serpent, or a wasp, or a lobster. I’m a human, most closely related to other humans with whom I share a common ancestor less than one million years ago8. Surely, it is more appropriate for me to be taking my moral lessons from the Son of Man than from another animal.

In the same exchange with Asa Gray, Charles Darwin writes,

On the other hand I cannot anyhow be contented to view this wonderful universe & especially the nature of man, & to conclude that everything is the result of brute force….I feel most deeply that the whole subject is too profound for the human intellect…. Let each man hope & believe what he can.

If I were to choose an animal as a moral metaphor, which one would it be? Something clever and cunning, like a medieval vision of a snake, telling stories in a garden about the virtue of selfishness; or like a dove, searching for an olive branch above a seemingly endless sea?

Peterson, Jordan. (2018) 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos. Random House Canada, Toronto, Canada. pp. 23 - 28.

Bracken-Grissom et al. (2014). “The Emergence of Lobsters: Phylogenetic Relationships, Morphological Evolution and Divergence Time Comparisons of an Ancient Group (Decapoda: Achelata, Astacidea, Glypheidea, Polychelida” Systematic Biology, 63(4):457–479. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syu008

Lavalli, Kari & Herrnkind, William. (2009). “Collective defense by spiny lobster (Panulirus argus) against triggerfish (Balistes capriscus): Effects of number of attackers and defenders.” New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 43: 15-28. doi: 10.1080/00288330909509978.

Childress et al., (2015). “ Are juvenile Caribbean spiny lobsters (Panulirus argus) becoming less social?” ICES Journal of Marine Science, 72(S1): i170 –i176. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsv045

I know most of this just from reading about these wasps on Wikipedia, seeking more information after one of the times I’ve been stung.

For a more complete description of this sequence of events, including pictures, see Sandor Christiano Buys, (2009) “Reproductive behaviour and larval development of Prionyx thomae (Fabricius) from Brazil,” Beiträge zur Entomologie = Contributions to Entomology 59: 311-317. DOI: 10.21248/contrib.entom ol.59.2.311-317

From the Darwin Correspondence Project at the University of Cambridge.

I am endlessly amused by how team evolutionary psychology likes to hold forth on the evolved similarities between humans and a variety of other animals, but obsesses over the differences between sexes and sometimes ethnic groups within our shared species in making their normative recommendations.

What a lovely meditation! I have not had the honor of witnessing birds in the nest and raising their young, but everywhere I have lived, they are marvelous. So too the various bugs, lizards, and snakes. Truly, there is treasure everywhere.

Those Panulirus lobsters need to get off their smart phones and social media.