The smart set

Religiosity, education, and belonging in the Caribbean and European Netherlands

My husband and I were invited to a really smart party, the kind with fancy catering and a bartender who’s been hired to make a theme cocktail for the event. I felt very cool and with-it.

A topic of conversation was our recent conversion to Catholicism. A Dutch lawyer in attendance was aghast: Why would we do such a thing, when we are both so well-educated? Isn’t it the case, he wondered aloud, that people only cling to religious superstitions when they don’t know any better? That as populations reach higher educational levels they shake off the blinders of belief in the supernatural? The host of the party, an American doctor, was rather more enthusiastic. “I am so, so happy for you,” he said. “Congratulations, and welcome home.”

I was thinking about this interaction at the Mass I attended later that week, where a quick back-of the-offering-envelope calculation indicated that about a quarter of the adults in attendance held an advanced degree. And then I read this article by Dr.

of the always-informative Graphs about Religion.

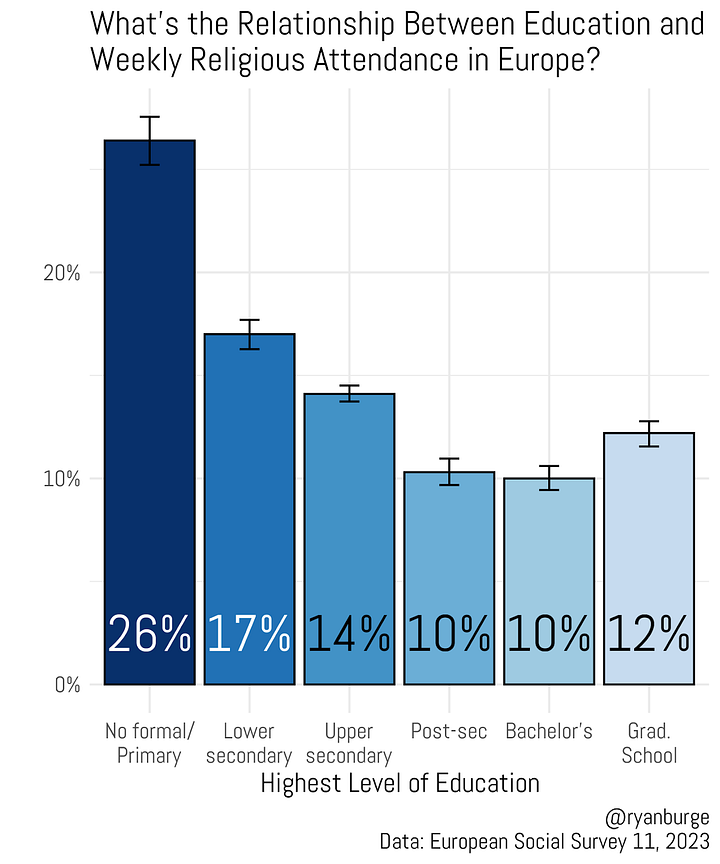

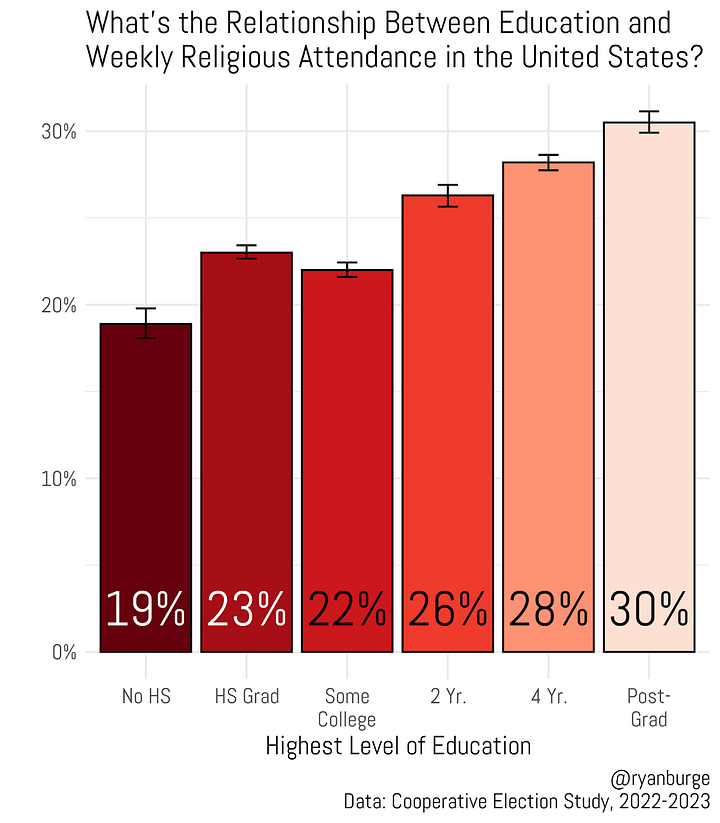

To summarize: Europeans are less likely to attend church services weekly than Americans are, and in Europe, higher education correlates with lower probability of attending church. In the United States, the opposite trend is seen. Not only is regular church-going more common in the United States than in Europe, but higher education also correlates with increased probability of attending church on a weekly basis. This analysis is based on data from the European Social Survey and the Cooperative Election Study in the United States.

So what pattern exists on my island, politically Dutch but culturally Caribbean, with the fascinating creole of indigenous, African, European, and American influences that entails? I went to Statistics Netherlands to find out.

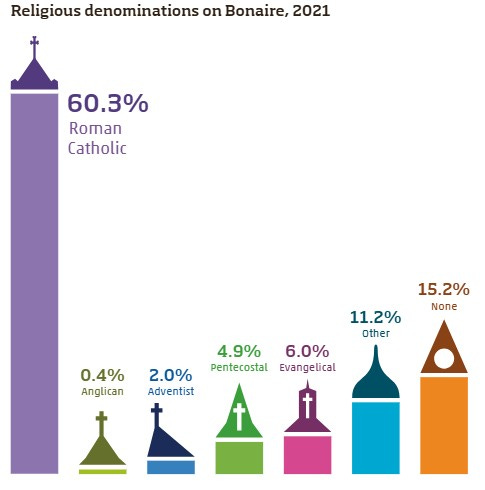

In The Caribbean Netherlands in Numbers 2023, it’s reported that supermajorities of adults living on the Dutch islands are religious—80% of my fellow Sabans and 85% of those on the larger island of Bonaire self-describe as belonging to a religion, almost all Christian. The largest group is Catholic.

According to the Dutch narrative surrounding education and religion, this may be because the islanders are a bunch of dummies. In a subsection helpfully titled “Lower educated more likely to be religious,” we are told:

On Bonaire and Saba, people with a low level of education are more likely to be religious than people with a high level of education. The biggest difference can be witnessed on Saba, where 92 percent of the population with a low education level are religious, against 72 percent of those with an intermediate or high education level.1 On St. Eustatius, more women (88 percent) than men (68 percent) are religious.

In the European Netherlands, a much smaller share of the population consider themselves to be part of a religious denomination or ideological group: 43 percent in 2022.

But are Dutch Caribbean islanders less educated than our European counterparts? The 2024 report from Statistics Netherlands reports information on educational levels for residents of the European Netherlands, but there is no comparable section in their annual reports for the Caribbean Netherlands. However, in a report on how happy we island people are despite our relative poverty and lack of social services, it’s stated:

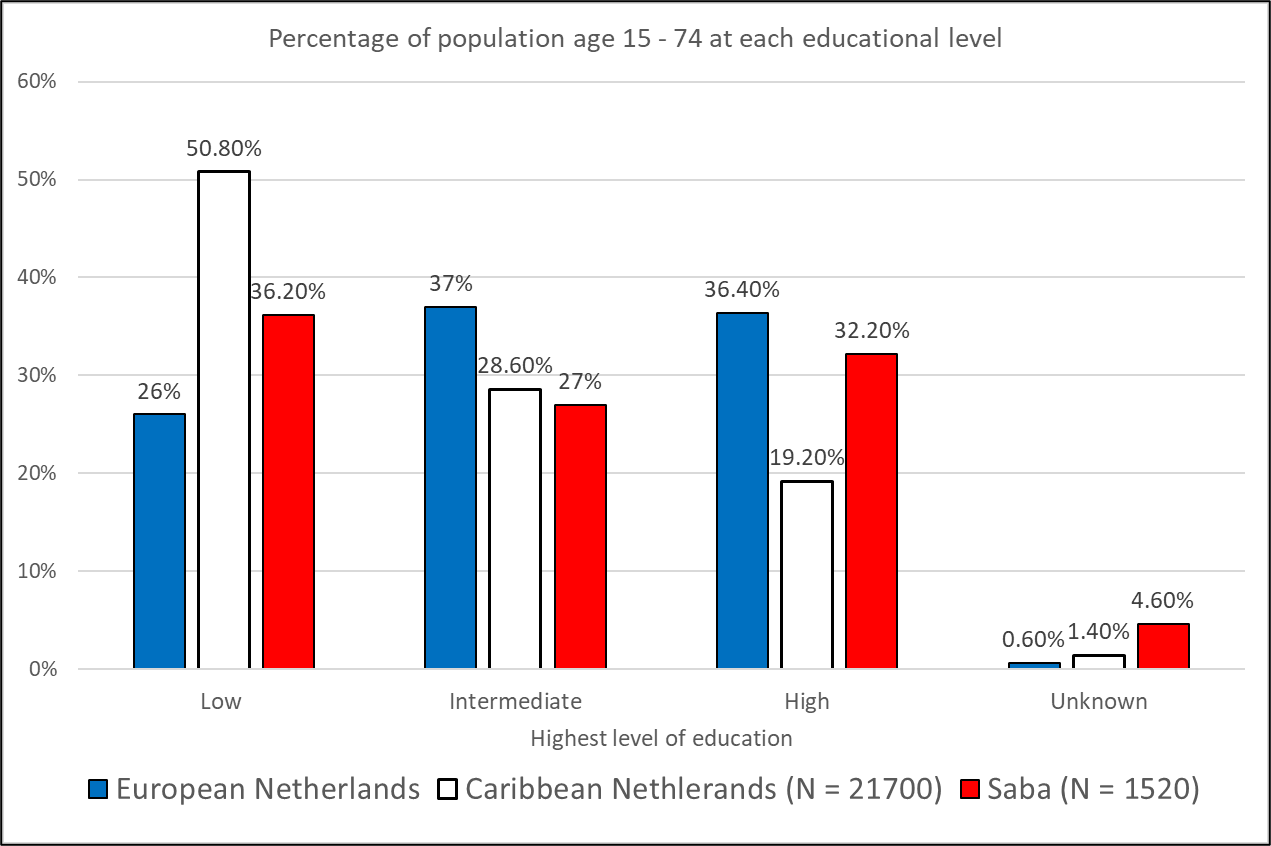

Relatively many people in the Caribbean Netherlands have a low level of education. This is especially true for Bonaire and St. Eustatius, where 50.5 and 61.7 percent respectively of the population aged 15 to 74 years had a low education level in 2022.

Spelunking around Statline, the searchable database for Statistics Netherlands, allowed me to find the raw data for this claim.

Defining these educational levels in American-friendly terms, a “low” educational level is the equivalent of a high-school diploma or less; “intermediate” is having completed some post-secondary school education, whether vocational or academic; and a “high” level is having completed at least some college coursework.

A greater percentage of islanders are at the lowest educational level than is seen in the European Netherlands, both in the Caribbean Netherlands broadly and on Saba specifically. Correspondingly, there’s a smaller percentage of islanders at the intermediate and high education levels compared to the the European Netherlands. The percentages of adults in the most highly educated group are comparable in the European Netherlands and on Saba, though.

But do they go to church? Or is it only those uneducated rubes who believe in God?

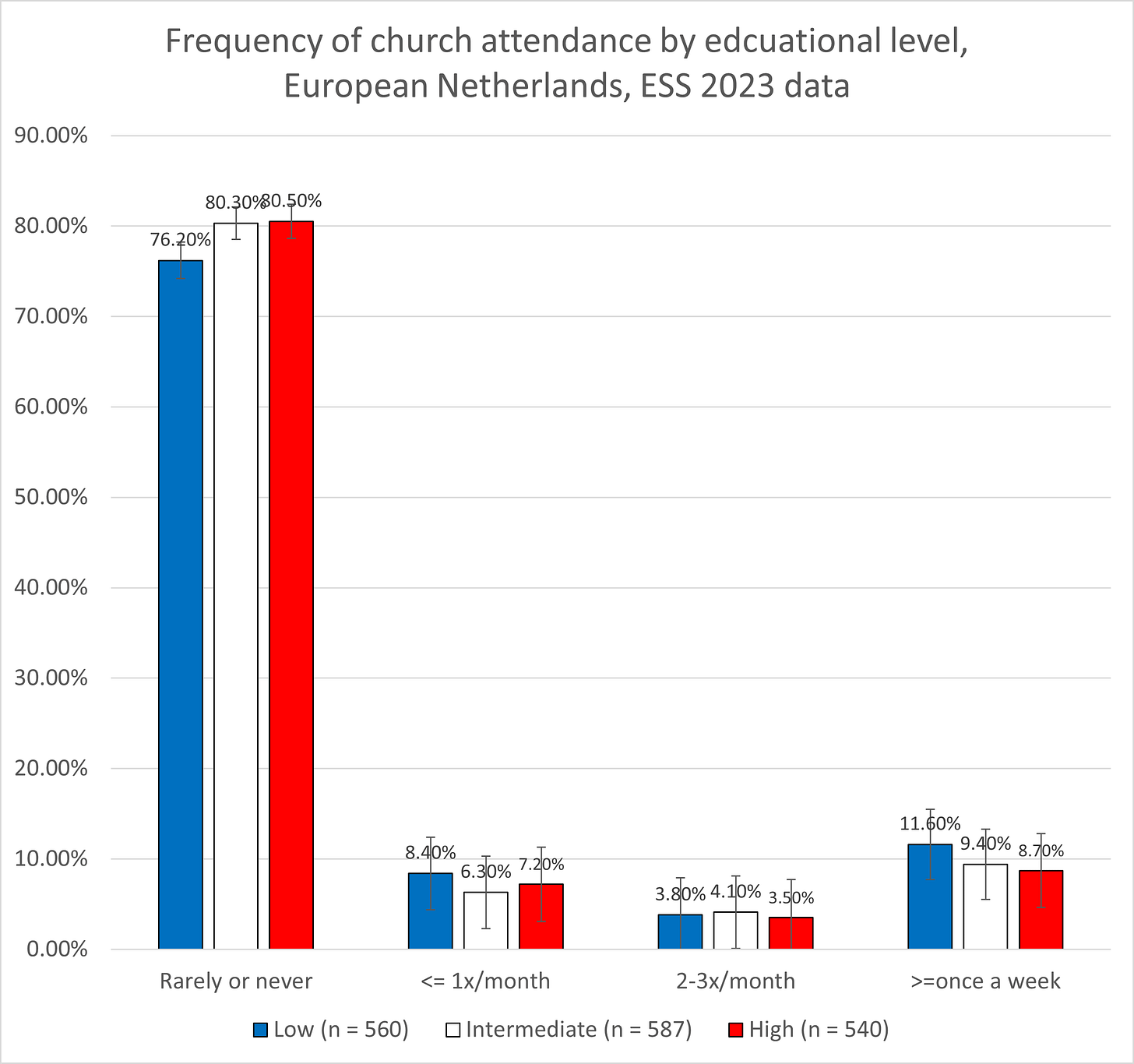

Well, in the European Netherlands, the smart set stays away from church services—just like members of every other educational strata. Statistics Netherlands hasn’t bothered to ask European Netherlanders about attendance at religious services since 2009, since so few people there go to church at all. But there’s not much difference between Statistics Netherlands’ church attendance data from 2009 and the more current data collected by the European Social Survey in 2023. Both then and now, upwards of 75% of the European Dutch rarely or never attend religious services—and education makes no difference in whether the European Dutch are likely to attend church.

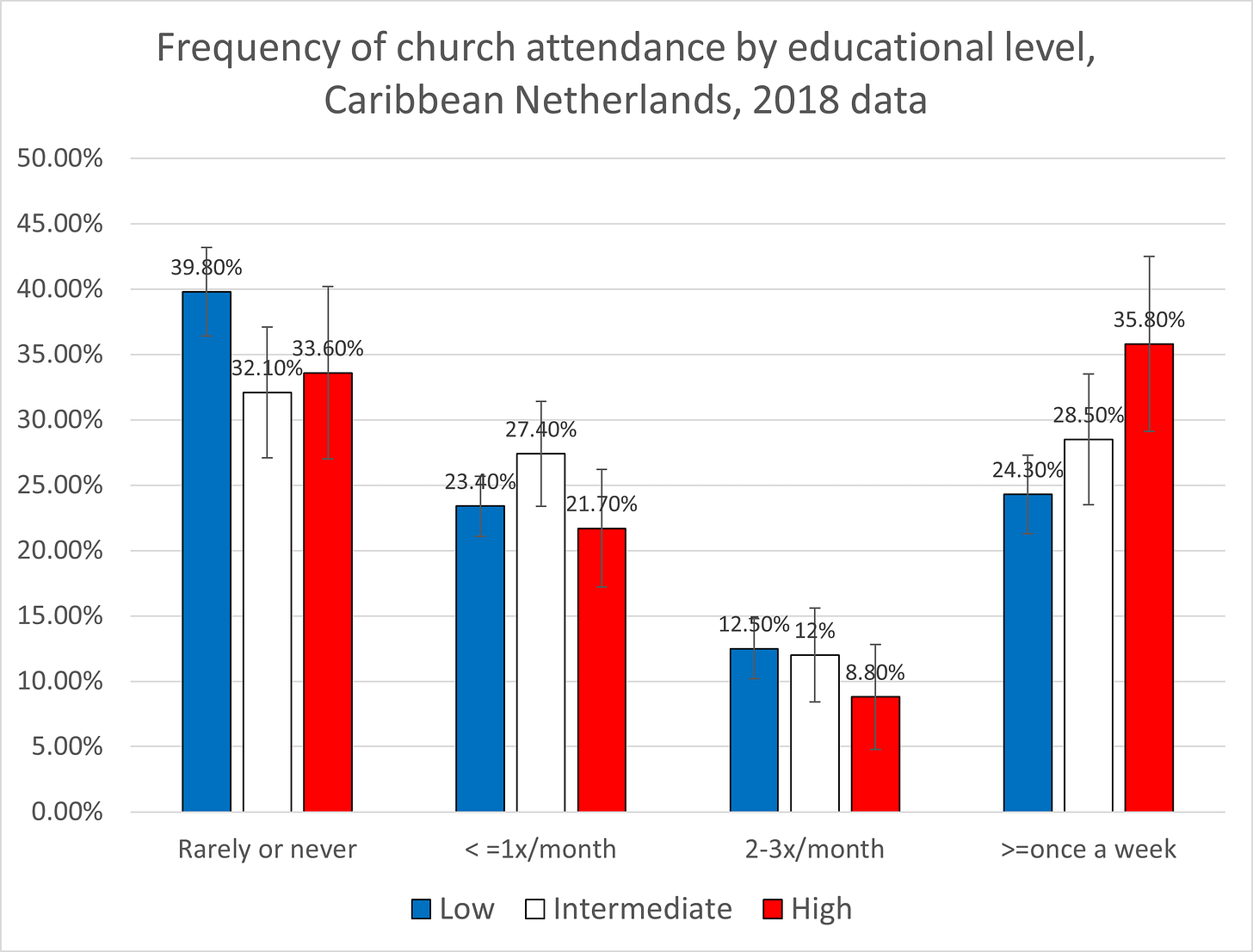

Meanwhile, in the Caribbean Netherlands2, there’s also not much difference in church attendance between the most and least educated, though we’re much more likely to attend church than the European Dutch are. About a third of the population of the Caribbean Netherlands rarely or never attends church, and about a quarter attends church less than once a month, with no significant differences among those with high, intermediate, or low levels of education. There is one statistically significant difference, though: those attending church every week are disproportionately likely to have the most education, with 35.8% of those with at least a college degree doing so. There’s a 10-point gap in the percentage of those who go to church every week between those with the least and those with the most education. Still, in the Caribbean Netherlands, almost a quarter of those with a high school degree or less attend church a minimum of once a week—a rate comparable to Americans with at least some college education in Dr. Burge’s research.

So patterns of religiosity by educational attainment in the Dutch Caribbean are much more American than they are Dutch. Of course, a lot of residents of the Caribbean Netherlands are American immigrants, myself included. For the Caribbean Netherlands overall, about one-third of the population was born outside of the Kingdom of the Netherlands; on my island of Saba, it’s more than half. On Saba, 12% of the population is North American by birth—more than double the number that were born in the European Netherlands. Others were born on other Caribbean islands, with about 10% of Saba residents having been born on Hispaniola. Still others were also born on tropical islands, but across the world in the Pacific. About 5% of Sabans are Filipino by birth.3

While the European Netherlands may be one of the least religious countries on Earth, the lands from which my fellow immigrants to Saba hail are some of the most Christian countries on Earth. Haiti and Dominican Republic are 96% and 83% Christian, respectively; the Philippines is 85% Christian4, with 38% of Filipinos attending church services at least once a week. It’s not surprising that patterns of religiosity on the Dutch Caribbean island of Saba are much more Caribbean than they are Dutch.

Attendees at Mass reflect that ethnic diversity and religious unity. The photograph below, taken at the celebration of Confirmation this past Fall, shows many native Sabans of a variety of races5, but also people born in the Philippines and Dominican Republic. Missing from this picture is anyone born in the European Netherlands.

The Dutch Caribbean is not just dominantly Christian, it’s dominantly Catholic. It’s easy to explain why the Latin American and Caribbean region in general is so Catholic: most of it was colonized by Catholic countries, like France, Spain and Portugal. This also explains why so many Caribbean islands have explicitly Catholic names6. It’s a little bit harder to explain why islands colonized by the Netherlands—a Protestant country with its own church at time time of colonization—are also Catholic.

As was the case with colonization of the rest of the Caribbean, profit was the main motive for Dutch colonization of the islands that would become the Dutch Caribbean. At the time of colonization, only one church was recognized by the state, the Dutch Reformed Church. But the smart set of the official church didn’t want anything to do with the enslaved Africans and indentured servants from Asia who had been shipped in to make the islands profitable. As Rose Mary Allen writes in Churches and faith on the Dutch Caribbean islands seen from the point of view of the agency of enslaved people7:

On these three islands, the Protestant Dutch did not want to allow enslaved people into their churches. From 1661 onwards, the WIC [West India Company, the Dutch corporation charged with colonizing the Caribbean by the Netherlands] turned a blind eye to Catholic priests being able to stay and preach temporarily in Curaçao.

On these nominally Protestant Dutch islands, it was left to the Catholics to evangelize to the masses of people who would make the islands their permanent home. When the West India Company overseers left, Catholicism stayed.

One of the reasons to join and to faithfully attend a church is to be part of a community. In the case of my husband and me, both raised Protestant, we started attending the Catholic church on Saba in part because we wanted to make Saba our home8. A good way to be part of a community is to do the things the community does. On Saba, one of those things is going to church. I think that this is one of the unifying forces that keeps our tiny island community together, despite the fact that over half of us are immigrants from somewhere else.

And I cannot help but notice that making Saba home is not the goal of the overwhelming majority of European Dutch who live here. Almost all of the roughly 100 people born in the European Netherlands who live on Saba now are on time-limited work contracts, typically with the government. The plan is that they will work on Saba for a year, or maybe two, and then go back to Europe, like a trader with the West India Company in times past. There is no intention of becoming a member of the community here. There is no incentive to do the things our community does.

In the European Netherlands, going to church is not necessary for being part of a community—and may even cut against it. But it’s simply not true that the European Dutch don’t go to church because they’re the smart set; they don’t go to church because in the European Netherlands that is simply not what one does.

Humans are social animals; we long to be part of a community. Once, as a young woman, I found solace for loneliness in thinking I was smart. I devoured works by Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, finding in New Atheism the comfort they mocked believers for finding in faith. Educated people, I was taught, do not believe in miracles or mysteries. And I wanted to be educated; I wanted to be part of the smart set. I understand how, in an increasingly lonely and dissociated world, imagining oneself to be part of a virtual community of brilliant believers in nothing might be alluring. If I had not moved here I can easily see myself falling into the same trap.

But through grace I fell onto an island where community is defined by something more than education level. On Sunday I will take Communion with people with graduate degrees and without high school diplomas, and be at home.

I note that a large fraction of adults in the “high” level of education category on Saba are temporary government employees imported from the European Netherlands, not native Sabans nor immigrants who plan to stay, discussed further below. I suspect that this may account for the observation made by Statistics Netherlands that the group with the highest level of education is “especially” likely to have no religion on Saba: much of the “high education” subpopulation is culturally European, not culturally Caribbean, while virtually no one in the “low” and “intermediate” education categories is a European import.

There is not enough data on church attendance specifically for Saba, with our population of 2060 people, for Statistics Netherlands to report it, which is why I’m showing data on religious attendance by educational level aggregated for all three islands of the Dutch Caribbean—Bonaire, St. Eustatius, and Saba—here.

“Race” plays differently in the Caribbean and in the Netherlands than it does in the United States. Native Saba families typically include members who would be categorized as both “white” and “black” in American accounting, because interracial marriage is incredibly common and has been for generations. Statistics Netherlands does not record race in its demographic data, either for the Caribbean Netherlands or for the European Netherlands.

Dominica and the Dominican Republic are both references to the Dominican order; there are also the Virgin Islands, a reference to the Virgin Mary; and of course the vast proliferation of Saints: St. Martin, St. Lucia, St. Barthelemy, St. Vincent, St. Kitts….

This is one of six essays in The Roman Catholic Church and the Dutch slavery past (2024) in Perspectief, Digital Ecumenical Theological Journal of the Catholic Association for Ecumenism.

But I converted because I came to believe that Catholicism is true.

This must be a cultural thing, which is more expected and less surprising from a Dutch European: What struck me about your story is how incredibly rude your fellow party goer seemed to me. Why would one say such a thing to a person who has just done something that is so deeply meaningful and takes so much work and dedication as converting to Catholicism? I'm not Catholic, myself -- I no longer even consider myself a Christian. After decades of consideration, I'm an agnostic who leans towards Buddhism. Still, I respect how meaningful many religions are to those who follow them, and Catholicism (which I have always admired even though, as I said, I don't feel connected to any Christian faith, myself) is a complex and deeply devoted faith. How could a person be so belittling of religion when they've just been told the person standing in front of them has accomplished so much in dedication to their own faith?

Then again, this makes me think of an American I once dated (Ron, who you met at least once, Rachel), an atheist who had lived in the European Netherlands for six years before I met him. At the time, I thought of him as an example of the kind of very smart but unearnedly arrogant young person who likes to hang out in coffee shops, writing bad poetry and contemplating the emptiness of existence, and who also feels very superior to anyone who isn't an atheist like themselves -- a very American way to be young, in my experience. But maybe it was even more Dutch European culture I was seeing in him?

A fine bit of journalism. Well done.